Confessions of a Female Badass is an ongoing column at Curtsies and Hand Grenades where I discuss women in genre cinema.

[TW: Discussions of Rape, Rape Revenge Movies, Incest and Rape Culture]

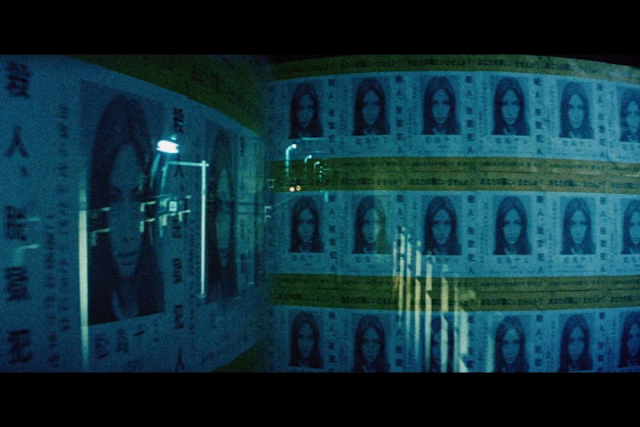

Female Prisoner Scorpion: Beast Stable would not be the implied conception of Themyscria at the close of Jailhouse 41. Instead of investing in the images of free women who are a collective force when brought together Best Stable opens with a metaphorical image that Scorpion (Meiko Kaji) would always carry her past and she’d continually be chased by the dogs of patriarchy. Over a brief sequence on a subway Scorpion is seen sitting alone before a group of police officers chase her out of the underground vehicle. One of those men is Detective Kondo (Mikio Narita), the man in charge of finding her. He manages to handcuff himself to the wanted criminal, but not before the subway doors are shut. This would leave Scorpion with just enough space to hack off his arm in a bloody heap. She runs through the station and the city with an arm trailing behind her. This image is in direct opposition to the image that closed Jailhouse 41. Scorpion is still running, but her pursuit towards freedom or safety is singular and she’s still dragging with her the men who long to see her punished for her crimes of murder. There is no wish-fulfillment in the land of beasts and the rabid tone of fiery vengeance in the previous two films is replaced almost entirely by an all encompassing, rain soaked melancholy. It’s an ironic choice to present the freedom of Scorpion as something ultimately doomed compared to the relative optimism in the predictability of her prison stay, but it’s a masterstroke in giving director Shunya Ito’s final Scorpion picture a heavy dose of reality and resets the stakes so that Scorpion has something to say beyond her vengeance. What Beast Stable marvelously accomplishes is setting up a secondary truth. We are not Scorpion, and some of us suffer regardless of some hope that we won’t.

Yuki (Yayoi Watanabe) is the figure with which that idea of suffering with no reprisal is presented. Yuki is an inherently tragic character beautifully acted by Yayoi Watanabe in what would be one of her only performances on film. Yuki is introduced by way of incestual rape. One of Shunya Ito’s greatest strengths as a director in this series has been his ability to clearly define the central figure of any given scene through blocking and camera work. This becomes especially important when you’re trying to shoot sequences of rape where it is incredibly difficult to retain point of view and intention. The Female Scorpion films in the hands of Ito have consistently given us a window into the horror of the act while still grounding us with the person this is happening to, and frequently these acts are part of a larger picture and not framed as the whole reasoning for revenge. In the previous film Jailhouse 41 none of the women featured were in jail for instances of revenge against rapists except Scorpion. By giving them a larger backstory they are rounded out in ways that make for interesting characterization. Oba (Kayoko Shirashi) in particular is one of the greatest characters in these movies, because she isn’t a saint, but you can see how she becomes who she is through both Scorpion’s eyes and her own. In Beast Stable Yuki is a great character, but it is with the assertion that rape has always been a part of her existence and she bares the scars of something that was never her fault. Yuki’s rape sequence is handled far differently than the other sequences in the Scorpion films; gone is the outlandish demonic faces of the abusers and the pained expression of a woman at their hands. Instead there is silence, darkness and a loss of expressiveness. There is no music to amplify the horror or frenzied camerawork to show struggle, but there is a calm acceptance of what is happening that is deafening in the blank face of Yuki. Ito shoots the scene with a few simple shots built around a couple of cuts to relay the language of the scene. There is an establishing shot of the landscape which looks like something out of Nagisa Oshima’s The Sun’s Burial and then an overhead shot of Yuki and her brother naked in a dark room. A close-up of Yuki’s face is then employed and it’s clear that she’s dissociated from the actions going on in her bedroom. These few shots are crisp, concise and introduce the audience to the central problem of incest for Yuki in a way that is not typical of exploitation’s usual tool-chest of sleazy over-statements and gratuitous nudity.

I am struck by the way Yayoi Watanabe approaches the role of Yuki as an insular person and how the camera always understands her own space through distance and estrangement. Yuki is characterized by sunken shoulders, recoiling posture and keeping her head down at all times. All of these actions present a person who doesn’t want to be touched, looked at or interacted with, and it is only considerate that the camera comply through medium and long shots. Even in the company of the city Yuki is framed in a way that presents her isolation by finding areas of quiet like an abandoned bridge, an alleyway or a graveyard. Through isolation Yuki can have some semblance of control over her body. She can shield herself from interactions, contact and conversation with other people and simply rest inside herself. She’s a loner by circumstance and survival. She comes home to her rapist so to find her own peace she has to find a nothingness in architecture where her safety is attainable. It’s reminiscent of what Sheryl Lee would do with body language so masterfully in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me. In that movie Laura collapsed inside of her own hell, and Sheryl played the role like someone grasping for a hand on the edge of darkness. When she was touched she reacted like a bundle of exposed nerves jolting into a reactionary refusal of interaction. David Lynch presented much of this through her already severely damaged headspace due to her own dealings with incestual rape. A lot of Laura Palmer’s eventual crumble is shown rather than implied differing her from Yuki’s situation, but where they share similarities is in the process of untangling themselves from reality to find peace in a solitary space that could be their own. For Laura Palmer that had to be achieved through death, but in Yuki’s case it is in the graveyard of her own mind, away, locked inside herself.

Yuki only finds Scorpion while strolling through the city trying to find a spot to hide her client and herself (Yuki’s a sex worker, another similarity with Laura Palmer). Scorpion is trying to untangle herself from the arm she chopped off in the opening scene of the movie. At first glance it looks like she’s gnawing at the arm until it relinquishes itself from the handcuffs, but she is merely dragging the cuffs across a headstone (a call back to her scraping knife in Jailhouse 41). Yuki is frightened by what she sees, but she and Scorpion have an understanding. They lock eyes and there is a cut to Scorpion free from the handcuffs sleeping at Yuki’s house. During this scene Scorpion meets Yuki’s rapist, and it turns out to be her brother who has brain damage from a working incident and cannot control his actions. This does not absolve him of his crimes, but Ito asks audiences to have empathy for the man in two images. One of which is achieved by placing the eye of the camera through his perspective when he attempts to rape Scorpion. This is the first time this has happened in these movies. The camera holds on his hands as they shake over Scorpion’s sleeping body, and it is a horrifying image, but also one of unsureness and skepticism. It is almost as if part of him knows this is wrong, and due to the knowledge of his damaged brain, it becomes a tragic scene. Scorpion fights back and the scene moves between their point of view until she grabs a knife and cuts Yuki’s brother. Before Scorpion can kill him Yuki walks in and she’s infuriated that her brother attempted to rape her new friend. She punches him and screams “Don’t I give you all the sex you could ask for? How could you?”. There’s a close-up of Scorpion’s face after this line of dialogue and Meiko Kaji’s acting here is noteworthy, because she lowers her guard and with her facial expressions she shifts the scene from anger to empathy, and her perspective is usually the one we follow. Yuki keeps her brother locked up in their house for fear that he may rape another woman. She carries a cross for the other women of this city she’s protecting by metaphorically taking bullets for them by absorbing the sexual assault of her brother. The greatest test of Scorpion’s ability as an avatar of Women everywhere (an idea presented in the second movie) is when she sees a woman like Yuki. Yuki obviously deserves to be free of her brother, but she is also the only person keeping him out of trouble and away from the streets. Yuki is a sacrificial lamb and Scorpion is a slaughterer, but when Scorpion sees the pain in Yuki’s face as they lock eyes she understands that Yuki doesn’t need revenge, she needs someone to understand, and as an audience we are supposed to as well.

This short scene is the most complex and daring in the entire Scorpion series because it asks us to understand the mindset of someone who is being raped by someone that they love. This scene is here to give Yuki more depth and place us even further into her world, a world she can barely control. It is here that the Scorpion series becomes more about Yuki than the iconic, titular character we’ve come to love. There is plenty of vengeance in the movie, but the emotional core of Beast Stable is in the face of a girl who can barely keep herself grounded on Earth. Yuki is a figure whose heart is pure, but has dealt with the most vile act and still comes out of it hoping for a brighter day. This is not to say that she doesn’t have her moments where she wishes her brother was dead, and there is a scene where she begs for that to happen, but she never acts on that desire. It is something I can’t possibly grasp, and it complicates Beast Stable because audiences are hardly asked to grapple with these questions. In the Jack Garfein film Something Wild (1961) a similar circumstance happens where after battling with post-traumatic stress disorder in the wake of being raped Mary Ann Robinson (Carroll Baker) ends up with another abuser only to live a life of domesticity. She is not persecuted for her actions in that film and Yuki isn’t persecuted here, but instead these films ask tough questions about the mindset of Women who have dealt with sexual assault. It is important to note that these movies contain a dense interior related to the physical self. They are burrowed in and so totally inside the body. They also don’t come up with any definitive answers on how to overcome the problem of having been raped, because there is no easy fix for survivors of sexual abuse. These movies instead let these Women decide what to do next and how to move forward if moving forward is even possible. It’s important that movies like Something Wild, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me and Female Prisoner Scorpion: Beast Stable remember the Women at the heart of their stories and never let the act of rape become something trivialized to a plot point or something secondary in these characters lives. When a movie is about rape it must wrangle with what this means and how this effects their characters in ways significant and minor. It cannot merely be background noise. In Female Prisoner Scorpion it is the catalyst for the suffering of Women everywhere. This movie understands it is about sexual power dynamics and the onus is unfairly on the Women to stop this action from happening which reflects the real world where we’re told to watch how much we drink at parties, not to walk down the wrong street or make sure our skirt isn’t too short.

The following day Yuki picks Scorpion up from her new job where she works as a seamstress, but something is amiss. Yuki greets Scorpion with a jubilant smile, but it almost instantly vanishes a second later, as if breaking her emotional consistency with happiness would undo her own sense of safety. She turns her back to Scorpion and there is a following close-up on the new friend’s face that reads as concerned. The tranquility of their near silent friendship is broken up by the feeling that Yuki is about to unleash a torrent of emotions, and that she is at her breaking point. Ito holds his camera on the two as they move through the city always making sure that the blocking is keeping in key with Yuki’s reluctance for intimacy and Scorpion’s distant compassion. Yuki always follows Scorpion and not the other way around, and when they sit and watch the sunset over a train station with a soda in hand a scene of possible dialogue becomes a moment of reflection. Scorpion is almost begging Yuki to open up through her glances and gestures towards compatibility, but her new friend is uncomfortable. When the two later end up at Scorpion’s apartment Yuki sits in the dark with her head down and she finally breaks the silence. “I’m not going home to my brother tonight. Let him starve for all I care”, but Scorpion isn’t buying her anger and tends to the groceries she just bought. Yuki then accelerates things and asks Scorpion to kill her brother, but bursts into tears seconds later. The final twist in the scene is that Yuki vomits after this reveal. She runs over to the sink to wash her mouth out before admitting that she’s pregnant. Her voice is heightened by her emotional upheaval and her strength in her own stoicism is ruptured by a pregnancy she doesn’t know how to process. A magical thing happens in the final frames of this scene. Scorpion gently rests her hand on Yuki’s back and out of Scorpion’s mouth she delicately says one word “Yuki”. It’s a gesture of pure intimacy that Yuki is not familiar with and we haven’t seen in the movie up to this point. Shunya Ito is consistently aware of what he’s doing with blocking and where his actors are in frame and in the case of Yuki she hasn’t been touched by anyone except for her brother up until this point. In the earlier scene where Yuki saves her brother from Scorpion’s blade there is an overhead shot of Yuki crouching beside her brother with a shadow splitting the image in half with Scorpion on the other side of the room. That image speaks multitudes of how her relationship to the world works. Yuki is essentially trapped by this unseeable barrier that makes her life one of near complete isolation. This is coupled in the fact that Yuki and Scorpion were always previously framed with space in mind on their walk back to her apartment. With this one single hand on Yuki’s back Scorpion shatters a wall and realizes Yuki’s potential to feel the touch of another human being again without it being rigid, painful and horrific.

Yuki is unfamiliar with that level of affection and sprints out of the apartment to get away from something she isn’t yet ready to embrace. On her way out a box of matches falls out of her purse that are slung into Scorpion’s chest by a man who crosses her off as she tries to catch up with Yuki. He’s not a man of subtlety and he removes his ridiculous sunglasses and licks his lips at the mere sight of Scorpion. What is revealed later is that this man works as security for the prostitution ring that later harms Yuki when she starts to work in their territory without permission. He slings the matches into Scorpion’s chest and walks away, but his body language and his intentions are clear in that he is using his power as a man to take possession and ownership of Scorpion’s body with a sexual advance and the severity with which he threw the matches back at Scorpion. The matches become a consistent theme throughout this movie as a symbol of the relationship between Yuki and Scorpion. The first of these images comes moments later in Scorpion’s apartment when she’s flicking the matches one by one and this is edited together with a scene of Yuki putting on lipstick for her job. This split POV enhances their relationship and makes the film feel symbiotic between the two women. The most striking moment occurs when Scorpion flicks a match and through that brief lighting of the flame a tear is visibly running down her cheek. Her face is otherwise emotionless, but this one moment of emotional significance from Kaji speaks volumes for her ability to convey with gestures both minimal and maximal. In the Arrow Video set Shunya Ito consistently compared her to Clint Eastwood’s The Man with No Name character from Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy, but she is much more complex than Eastwood’s iconic gruffness and infinite cool. She is instead a towering figure of empathy, motherhood, and warmth funneled through a psychedelica that owes debts to Seijun Suzuki, Nagisa Oshima and an emotional wellspring that is closer to Maria Falconetti in her ability to convey a total facial performance

The previous two films in the Female Scorpion franchise had to deal with genre expectations that bridged the gap between genres such as horror, rape-revenge, women in prison and women on the run. These movies had a duty to cross off certain elements on a checklist in order to be made, and for the most part these movies succeed at taking these genre limitations and turning them into strengths. For Female Prisoner Scorpion: Beast Stable those expectations are gone in favour of a freedom that gave Shunya Ito and company the permission to run wild with what they wanted to portray to an extent. However, with the diminishing need for genre fulfillment there was a new one for sequel expectations that handcuffs Scorpion slightly. Ironically the thing that gets in the way of what Beast Stable wants to accomplish is the actual act of vengeance, which was the core of the previous two movies. The vengeance in Beast Stable is closer to a digression, but like the previous two films this obligation becomes a strength, because they didn’t sleepwalk through this part of the filmmaking process or anything else.

The vengeance that must be fulfilled in Beast Stable is tied together through a few coincidences that link the characters of Yuki, Scorpion and a third woman who isn’t named. This final woman is introduced shortly after Scorpion’s run in with the man in her apartment complex and like Yuki she is a sex worker and she is pregnant. She’s hiding the pregnancy from her bosses, but eventually begins to show. Katsu (Reisen Lee) runs the show in this side of town controlling the sex work game and her many security officers find out about this woman’s pregnancy and bring her to Katsu. Katsu is a figure of exaggeration with garish make-up closer to the styles of 70s drag queens and she lives with a flock of crows who hold no significance other than to paint her as an elaborate creature of strange taste. Around the same time the man who threatened Scorpion in the hotel dies, but not from her hand instead it’s from another woman, but Scorpion is assumed to have killed the security officer. The men who work for Katsu capture Scorpion at the same time they are punishing this third woman. They see her pregnancy as a loss of finance and force her to have an abortion. Yuki plays into these narrative threads through her own interaction with Katsu which ended in torture for having worked in her area without permission, and with her own pregnancy.

These rather cumbersome plot coincidences are handled with some level of grace through expert filmmaking and two scenes which are elegant, extreme and emotionally thunderous. The first of which is the forced abortion which is cut parallel with Yuki’s which was of her own free will. The forced abortion is one of total horror. It is a scene of annihilation. The room is sheathed in white with curtains, tables and walls all projecting this perceived cleanliness, but what is happening to this woman is anything but and her blood ruptures the paleness of the room. Her voice is like an alarm, heaving and moaning with guttural intonations that reckon with the complete sorrow of a motherhood lost. The sort of camerawork that was used in 701 and Jailhouse to convey rape is used as well, and it makes sense that these techniques that worked so well in those previous two movies would work well here, because both scenes are used to show someone taking something from another person. There’s a close-up of her face that elicits such total pain it would be easy to miss that she grips a scalpel, but this too is in frame and leads into the single most powerful image in the whole of the Scorpion series.

In an interview with Arrow Video Shunya Ito stated that Luis Bunuel was one of his favourite directors and the recurring blade across the eyes image is an homage to Un Chien Andalou. In Jailhouse 41 Scorpion witnesses the death of an old woman who in her final moments gives Scorpion a knife. After she is given that weapon the old woman dies and is buried underneath the autumn leaves after a deep gust of wind and then vanishes. Upon seeing this Scorpion takes that blade and runs it across her eyes and in that moment she became mystical and endowed with an assumed power to complete her tasks of vengeance at all costs due to the spirits of Women scorned. Beast Stable uses this image too, but Scorpion’s possession is given so much more weight due to what we’ve seen happen to the woman who gives her the scalpel. After her abortion the unnamed woman is brought back to Katsu’s lair to die, but inches away from her is Scorpion being held captive for her assumed murder of one of their security guards. Scorpion notices the woman edging closer and closer so she dangles her arm out of the cage and they touch. Scorpion’s gesture gives this dying woman a last moment of assurance that what she has experienced will not go unpunished. With that outstretched arm Scorpion unfurls finger by finger the scalpel she grasped when they took what would be her child. Scorpion’s hands shake and she pulls the scalpel out of her hand. In an extreme close-up reminiscent of what Jonathan Demme would popularize years later in The Silence of the Lambs she takes that scalpel and drags it across her eyes. Meiko Kaji’s eyes are the window to the soul of these movies and an audience surrogate. Her eyes are bleary, bloodshot and about to burst with tears for what she has seen. She slowly pulls the blade across and the tears start to roll out, and it is in the intensity of her stare and the sorrow of the previous scene that makes this moment of action have context the previous usage of this image did not. Here, Scorpion becomes a reaper in a way that doesn’t ring as abstract or showy, but simply through the tools of cinema that have been apparent since the silent age, an image, a face and a reaction.

Yuki’s own abortion runs in syncopation with the unknown woman’s and gives an added dose of fuel to the revenge that Scorpion proceeds to unleash after she becomes possessed with the spirit of the dead mother. The idea of the inserted vengeance narrative inside of Beast Stable comes out of an analysis of how motherhood is perceived in the world in which they live. The narrative logs that form the bridge here are that rape can lead to unwanted pregnancy and how does abortion tie into this story? We never learn the unnamed Woman’s backstory, but it is assumed she is happy with her pregnancy, unlike Yuki, and they represent the opposite spectrum of how pregnancy is presented. On one hand Yuki’s fetus is the product of incest and she struggles with the notion of keeping or terminating the pregnancy, and she eventually decides to abort. The other woman is faced with the horror of not deciding what to do with her body, and her decision is made for her. This implies that Beast Stable is a pro-choice movie, and this perception is achieved through the simple parallel editing of how their abortions are performed.The Scorpion films ask these questions of what constitutes having a female body at its worst, and the growth in these movies is that this feeling has shifted slowly from an external idea of what femininity looks like to something internal and true due to the faces, body language and sheer presence of Meiko Kaji, Yayoi Watanabe and Kayoko Shiraishi.

Upon killing the men who forced the woman to have an abortion Scorpion says she’s possessed with the spirit of the dead girl, and what was assumed to be implied regarding Scorpion’s powers is confirmed, but her powers only give her so much, and she soon finds herself retreating from Detective Kondo and his men who want to see her die. Scorpion crawls into a sewer to hide, and what started in a damp hell would end there. In Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion she was sent to live in a dungeon of the prison where the floor was wet, cold and there was no light to creep through the darkness. In Beast Stable Yuki provides the light by dropping matches down the sewer and calling her name.

“Sasoriiiiiiiiii”

To call Scorpion’s name is to bring her to life, and the magic of watching the Female Prisoner Scorpion movies is in the belief that she’d appear. The idea of Scorpion is one of both justice and freedom that a woman isn’t alone and her heart can sing even when hell surrounds her. Meiko Kaji brought Scorpion to life through her steely gaze and her empathetic trust in the fruitfulness of women through her cinematic actions, both violent and affectionate. She created a figure of light and darkness that could take up a sword for the damaged or offer a healing hand when necessary. Kaji sings the theme song that plays throughout these movies and the lyrics say “A Woman’s life is her song” and my song is one of survival. Upon finishing Female Prisoner Scorpion: Beast Stable I came clean with a secret that I had harbored inside of me for a very long time. I sobbed on my husband’s shoulder and told him that my father raped me on a semi-regular basis while I was growing up. The experience of actually vocalizing my history with sexual abuse was a moment of healing, because I could finally begin to understand that I did nothing wrong, and I didn’t bring this on myself. Watching the Female Prisoner Scorpion movies has been a cathartic experience for my soul and having been open about my past I feel like I am able to move forward with my future. I saw something of myself in Yuki and I felt attached to her as she dropped matches down into the sewer calling her saviours name, and I knew that I had something of a saviour in Scorpion. The very idea of her was with me and even in knowing I’ll always drag my past around, she has given me the strength to pick up the pieces of my own life in some small way.

Be First to Comment