[TW: Detailed account of sexual abuse]

[Spoilers: Twin Peaks, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, and Twin Peaks: The Return]

My angel does heroin,

It could be called a home,

For someone who never heard bed time stories,

She doesn’t know happily ever after

Only a window

My angel was raped

Her best Sunday dress

burned in effigy

My angel doesn’t have a saviour

Only a heavenly father

Daddy’s little girl

My angel is crimson

Too unclean to ever be a lamb

Only ever a second thought

My angel waits

her gaze lingering

an image of a bedroom door

Turning,

a light shining through

Leaning, Leaning

On the Everlasting Arms

My angel screams

and I listen

-An excerpt from my journal. Written the morning after Twin Peaks ended

I sit in the darkness of my bedroom, staring at posters I have plastered all over my walls, looking at the door and wondering if I’d get to sleep that night. Sometimes I’d get peace, but sometimes the door would crack open and monsters would come inside. That’s how I internalized what was happening to me when I was younger, but when I grew up I had the knowledge to put it into words: incest. My father knew that I was feminine. He knew before anyone else. In an attempt to curb my own fascination with things like dresses and makeup he would come into my room, abuse me and mutter things like “this is what happens to women. Do you want this?”. Mourning the death of his son, and destroying his daughter. It was an attempt to control my body. It was power and dominance. That’s all rape is, but in addition to taking my body he took my family, and my home. There was no sanctuary. A wounded animal returns to its home when they know they’re about to die, but I had no such place, because my predator stalked in my own bedroom. Laura Palmer is the single most important character in all of film or television for me, because she knew this feeling too.

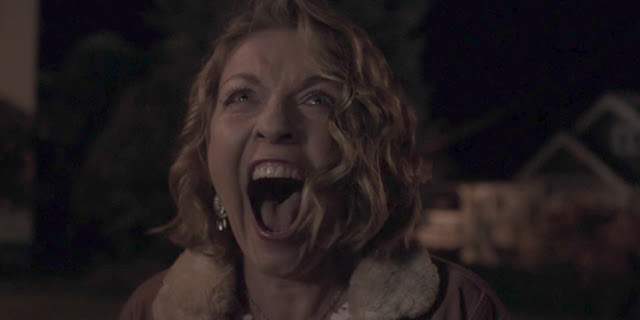

A mother (Grace Zabriskie) caught in the reverberations of a traumatic whirlpool wallows drunkenly into frame, taking a picture of the prom queen who was her daughter (Sheryl Lee) by hand and smashing it into the floor. Twenty five years earlier, a father (Ray Wise) cradles that same picture and dances with the photo, with the prom queen’s face always present in his outstretched arms. The mother grips a piece of shattered glass in hand and plunges it into the image of her daughters face repeatedly, wailing, screaming and echoing the primal upheaval that has reshaped her entire life into a cesspool of damnation, by way of grief. The camera idles closely to her, slowly zooming, until we see the fractured image of her daughter torn to shreds. Twenty Five years earlier, that same father rapes his daughter, and she is murdered by his hand. The image of Laura Palmer, and by extension Sheryl Lee, in the work of David Lynch, is one of dissonance. She’s the perfect good girl (as described by Jennifer Lynch in The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer) and the tormented martyr who chose to die. In Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992) she was laid to rest, finally, peacefully, given an angel. Laura was saved by her decision to succumb to death with the introduction of a supernatural ring she slipped on her finger, which trapped herself in a heavenly space. She was away from BOB, her father and David Lynch. But it is happening again.

The soul of Laura Palmer has lingered throughout the career of David Lynch ever since her body was found wrapped in plastic on a cold shore in the sleepy town of Twin Peaks. She has haunted the filmmaker, much in the same way she has Special Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle McLachlan). Cooper is a manifestation of David Lynch’s obsession to consistently return to Twin Peaks in the desperate hope of saving the girl who began as a corpse, and slowly evolved into a messianic image of grace.

Lynch has a warehouse of actors he loves to work with who each have their own contextual relevance within his art, but Sheryl Lee holds a special place. She is the martyr in which David Lynch funnels his greatest streaks of empathy for humanity’s unfairly damned. Nearly every woman in the work of David Lynch since Twin Peaks has been a manifestation of Laura Palmer in some way. In Mulholland Drive (2001) Betty (Naomi Watts) is a goodhearted person attempting to help another woman in need, while also trying to make it big in Hollywood, but is poisoned by the toxicity that rests within the system. Nikki (Laura Dern) is also an actress, but her reality is unfairly ripped apart by a cursed film script which she dared to verbalize in Inland Empire (2006). Both of these women are pummeled by gendered violence: a trope that lingers in the blood of all of his motion pictures, and they are all in a sorority with Laura Palmer: the girl he couldn’t save.

Even in the beginning of Laura Palmer’s imagery in the work of America’s greatest surrealist filmmaker, Lynch showed a grief in the destruction of this poor girl. In the pilot of Twin Peaks the melodramtic reveal of Laura’s dead body is later proceeded by near constant images of family and friends sobbing hysterically over this girl they loved. Everyone was in grief over her death, whether they realized it or not. They were mourning her, but they were also despondent over the death of their own town. For with Laura’s death, so went the soul of small town America, but what Lynch wants us to know is that there was no soul there to begin with, and there was always horror behind closed doors. It was the case in Blue Velvet (1986) when doe-eyed boyscout Jefferey Beaumont (Kyle McLachlan) peaked behind the curtain of a nightmare with perverse interest, and it was the same here. There’s always horror behind the suburban image of the American subconscious, but we hardly ever want to fully reckon with these things, because we want to act like fathers aren’t capable of raping their own children. Twin Peaks is honest in pointing out the rot at the centre and the show is still dealing with the ramifications of that knowledge. “How could this happen? Did you even want to know?” To paraphrase a statement between FBI agent Albert Rosenfeld (Miguel Ferrer) and Special Agent Dale Cooper at the close of the Laura Palmer investigation back in season two. They ask who BOB might be, and ponder if he’s a supernatural entity, and whether or not Laura’s father may have been innocent at heart. Maybe Bob’s just the evil that men do, but that would require us to ignore that men do evil.

One of the first images of Twin Peaks: The Return recontextualizes the moment from the Pilot where Laura’s best friend, Donna (Lara Flyn Boyle) notices an unnamed, faceless high school girl running across the school’s front lawn screaming, but now it is a slow motion image (later again in Black and White) with a deafening howl that would foreshadow a show gripped with the pain of Laura Palmer’s lingering trauma and the death that changed Twin Peaks forever. This is blood that stains eternal, and horror that doesn’t leave once its nested in the body of small town America.

Laura Palmer is the only innocent in the wake of all this tragedy. In the work of David Lynch the image of Sheryl Lee and Laura Palmer outside of Twin Peaks rings with angelic grace. In Wild at Heart (1990), Sailor (Nicolas Cage) and Lula (Laura Dern) are starstruck lovers pulled apart by circumstances completely out of their control, but throughout it all, their love persists. It’s perhaps Lynch’s most simplistic film in terms of plot, following a linear, if jagged, path from sweeping romantic love, to heartbreak and back again, bathed in the romanticism of 1950s culture, and fused onto a distinctly 1990s backdrop and flavour. Near the end of the film, after Sailor has gotten out of prison, he meets up with Lula once more only to break her heart, and tell her they can’t be together, but an angel intervenes in the way of David Lynch’s own Glenda the Good Witch played by none other than Sheryl Lee. David Lynch is obsessed with The Wizard of Oz going as far as to call it a “life-changing film” in Chris Rodley’s career-spanning book of interviews with the filmmaker, Lynch on Lynch. Sheryl, as Glenda, convinces Sailor to go back to Lula, thus being a guardian angel for two potentially brokenhearted souls. In Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, all Laura ever wanted was an angel.

The image of Sheryl Lee as a pure force and catalyst for good in Wild at Heart is not unlike the image of Lee in episode 8 of Twin Peaks: The Return where the image of prom queen Laura Palmer is surrounded in an orb of effervescent golden light. In the context of the nuclear horrors and origin story of BOB earlier in the episode, it creates a fulcrum where Laura is the one sacred image in the world of Twin Peaks, and by extension, in the work of David Lynch. She is a Joan the Maiden figure; a crystallization of Lynch’s key interest in redemption through violence, and the unfairly maligned purity of a girl who does not deserve her fate, but nevertheless falls in the wake of such horror.

II. There’s Fire Where You’re Going

David Lynch is but a single artist, and the sheer power of Laura Palmer’s presence would not shake with totemic magnitude if not for the unparalleled work of Sheryl Lee in the Twin Peaks narrative. She has haunted the series ever since her face was revealed in the opening moments of the pilot for Twin Peaks. Her mere appearance was enough to rock the foundations and preconceptions of what audiences in the early 90s considered fun, kitschy, Americana. The series was never about its eccentricities. They existed on the surface as a way to lull viewers into a false sense of security. They would believe that within the centre of Twin Peaks, there too would be goodness, but at its heart Twin Peaks is a series about trauma, and the lingering, generational effects it can have on a personal level, and a more widespread community. Nothing within Twin Peaks exists only within itself, when we know that hidden beneath the plaid skirts, mugs of damn good coffee and cherry pie there was a dead girl, and her name was Laura Palmer. Sheryl Lee would be the only catalyst in which she could come to life and give this series meaning. Ironically, when she was given a chance to finally speak in the prequel film, Fire Walk With Me, her truth was ignored by audiences and critics alike. No one saw Laura Palmer. Not in Twin Peaks. Not in the film community. Not on planet earth. At her funeral her former boyfriend Bobby Briggs (Dana Ashbrook) screamed that “she was in trouble, and no one bothered to help her. We all killed her”. These words were gospel, and at the time Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me was considered the biggest failure of David Lynch’s career.

What lives inside Fire Walk With Me is the unbridled, brutal honesty of a girl suffering at the hands of incest. When we’re first introduced to Laura Palmer in Fire Walk with Me it is through a tracking shot. It’s jolting and startling to see the image of the girl who washed up on the shore given life. No longer an object. She’s living, breathing, and going to school just like everyone else, but there’s something subtly off about the way she carries herself, as if her body is functioning on auto-pilot, while her mind races away somewhere else. She trudges more than walks, and her awkward, if sweet, interactions with a fresh faced Donna Hayward, now played by Moira Kelly, create an immediate dissonance between the two characters. There is no way for viewers to see Laura Palmer without the context of the image of the dead girl, and Sheryl Lee understands that central idea in her body language. As if, she too, understands her place in the world is one of temporary residence. No one lives, but usually we do not resign ourselves to death in the way that Laura Palmer has as a result of years of sexual abuse. She carries the grief, disgust, self-hatred, and exhaustion of someone whose body is out of their very control. There isn’t a way to understand what a body is, if you’ve never been given the opportunity to live in your own skin, without someone taking everything from you. Since the onset of puberty Laura has been violated, and with the ongoing changes in her body she has seen a world that views her through the same lens her abuser does. The eye of David Lynch’s camera lingers, letting Sheryl Lee’s performance do the talking, leaning inward when necessary to create the illusion that there isn’t space between the audience and Laura Palmer. It is up to us to feel empathy for her and listen to her cries. She cannot be ignored like Bobby said she was at her looming funeral. We have to see her.

The true depth of Sheryl Lee’s performance is the entire reason Fire Walk With Me resonates. In this film she casts a shadow in which every other actor in the work of David Lynch must stand. “The Girl in Trouble” being Lynch’s favourite narrative pathway, means that all the women who live in his cinematic world are torchbearers of Laura’s poor soul. Sheryl’s performance is mostly realized within her facial reactions and physicality. Extreme close-ups are occasionally employed to amplify the sorrowful look held deep in her eyes, or the gulp that slides down her throat before saying “There wouldn’t be any angels to save you” when talking to Donna about floating in space. Sheryl Lee plays the role with an agonizing closeness, her fragile body imbued with the realization that what’s happening to her will never stop. She’s too far down the rabbit hole and there’s no waking up for Alice. Death becomes a constant fixture within her thought process. In The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer Laura thinks about death as a release from her day to day violence, both self-inflicted and by others. Sheryl Lee took the textbook written by Jennifer Lynch and wrangled the soul of Twin Peaks away from David Lynch, Kyle McLachlan or Dale Cooper and fixated it firmly within this girl dying from incest. She gave Laura dexterity, life and dreams beyond the corpse she would become. Her struggles rang true for girls like me, who experienced incest. Girls who burn brighter in the dark.

Laura chose to die. It is the only way she can grasp at any sort of agency in her own life, beyond numbing herself out on drugs and alcohol. When she eventually meets BOB//Leland in the abandoned train car her arms are tied behind her back, further stripping her of any sort of defensive maneuvering. She wrote frequently in her diary that she knew the day she’d die was coming, as BOB’s attacks grew more violent and enraged. In the Secret Diary some 15 pages or so have been ripped from existence. The missing pages are BOB’s admittance of defeat. He’s afraid, tortured of a girl growing more aware, and stronger, through her realization that to give herself and her body up meant BOB could no longer have his twisted idea of fun. Laura’s decision to die grants her the ability to have a body for what could be the first time in her life. This is co-signed through visual imagery, both in Fire Walk With Me and the pilot for Twin Peaks. In Fire Walk With Me it’s her cathartic realization that she’s in a heavenly space when an angel hovers over her. The angel is a protective symbol for Laura, due to her fondness for a painting of a similar angel that hung in her bedroom. In the pilot, it’s the reveal of her body, a complicated image due to her lifelessness, but upon Laura’s face is an expression that isn’t trapped in fear or wracked with tears, but one of rest. A close-up of her grey, decaying face summons the rapturous crescendo of Angelo Badalamenti’s score further cementing the idea that this is a moment of peace. A smile, because it’s over, but it wasn’t.

And I wait, staring at the Northern Star

I’m afraid it won’t lead me anywhere

He’s so cold he will ruin the world tonight

All the angels kneel into the Northern Lights

Kneel into the frozen lights

And they paid, I cry and cry for you

Ghosts that haunt you with their sorrow

I cried ’cause you were doomed

Praying to the wound that swallows

All that’s cold and cruel

Can you see the trees, charity and gratitude

They run to the pines

It’s black in here blot out the sun

And run to the pines

Our misery runs wild and free

And I knew, the fire and the ashes of his grace…

-Courtney Love, Northern Star, 1998

On October 3rd, 2014, David Lynch and Mark Frost simultaneously tweeted “That Gum you like is going to come back in style. #damngoodcoffee” This joint message sent film fanatics and die hard Twin Peaks fans into a frenzy. Was the show coming back? Was there going to be a movie? Could all of this be real? We all desperately wanted David Lynch to return to the cult phenomenon, but we never asked ourselves what the price of that would be. We were full speed ahead, no matter the costs. The coffee, Audrey’s dancing, Special Agent Dale Cooper, all of it would be, not only nostalgia for the weird, but a new passion project from one of Cinema’s finest directors. We didn’t know what we were getting ourselves into, and that was exciting. What happened was something we could have never expected, which was unsurprising in some regards, but the connotations of what David Lynch and Mark Frost had actually cooked up had deeper ramifications for the universe they created together in the late 80s, and on the image and body of Laura Palmer.

In tenth episode of Twin Peaks: The Return there is a long scene where The Log Lady (Catherine Coulson) not so cryptically tells Deputy Hawk (Michael Horse) about Laura. She tells him that “Laura is the one” and to remember that information. It is a mission statement if anything on the true nature of Twin Peaks and the work of David Lynch as a whole. Everything traces back to her and runs through her narrative and image. She is the image over the credits. She’s the body that washed up on shore. She started it all. Any connotations of Cooper’s narrative or how he would get back into his body after BOB invaded, in the series finale of the original run are smokescreens for the actual mystery of Twin Peaks. Lynch is on record as saying he would have never solved the mystery of Who Killed Laura Palmer? If it had been in his hands. Showtime gave him that opportunity and with it recontextualized the very nature of many previous images in the lexicon of Twin Peaks. The most notable of which being Laura’s happy ending in Fire Walk With Me, which is now whisked away into a temporary place of satisfaction rather than a permanence of tranquility. Dale Cooper, in his over-eagerness throughout the entire run of Twin Peaks to save Laura Palmer, misunderstood the entire basis for her messages to him. Laura didn’t need saving. She needed justice. She told him as much in The Red Room, but he couldn’t remember who Laura’s killer was. He didn’t listen.

This continues in the most recent incarnation of David Lynch’s masterwork, where Cooper, being personified through Lynch’s willingness to keep the aura of Laura alive, undoes the very thing she achieved in her final moments. In episode seventeen of the revival, through the shows mythology on electricity and alternate dimensions, Dale Cooper finds himself hiding in the bushes, moments before Laura walks to the haunted train car where she would die. He steps out of the shadows and guides her by hand. Dale says that he wants to take Laura “home”, but for an incest victim there is no home. Home is the point of trauma. Home is the point of total loss. If your family DNA is the connective tissue which gives you life then that is burnt by fire and turned to ash when the very person who helped bring you into the world fractures your very existence. Dale Cooper does not understand this and after a momentary walk through the Douglas Firs Laura vanishes, the only thing left being an echo of a scream. Her destiny is altered and thus her image. Her body never washes up on shore. Pete Martell (Jack Nance) goes fishing, Josie Packard (Joan Chen) applies makeup, Laura never dies. This is not a moment of reconciliation and joy for anyone. It is a failure, a stripping of her agency and a true death.

The image of Sheryl Lee as Laura Palmer is further complicated by the following, final hour of Lynch’s magnum opus when Cooper tries once more to bring Laura Palmer home in an alternate version of the world he used to reside. When he comes into contact with Laura, now going by the name Carrie Page, he insists that he’s an FBI agent and he needs to bring her to Twin Peaks, Washington. She’s unsure of this man, but either through a familiar recollection of Cooper’s face or the fact that she needs to get out of dodge anyway she follows. And they travel down the darkened road of America with only headlights to guide them through the tar. Something immediately feels off in this silence, this Cooper and this reality. The sense of dread can be felt in the abandoned buildings they drive past. This is a dead world. When they cross the bridge into Twin Peaks there’s something immediately wrong. Carrie doesn’t recognize any of it, and as they get closer to her alternate reality childhood home there is still nothing to remark upon. This doesn’t change when they ring the doorbell, talk to the owners or step away from the house. It is a failure on Cooper’s part to bring her here and while Carrie tries to console him, Cooper finally says something that unlocks the repressed memory of Carrie Page and Laura Palmer. “What year is this?”. The camera sits firmly on Laura’s face as she beings to crack. There’s a cut back to the house where Sarah Palmer can be heard saying “Laura?!” and then everything falls. She screams, her face stricken with complete horror. The lights go out on the world, and Laura Palmer dies again.

The essence of this final sequence is one of a lingering trauma within the heart of Twin Peaks. Dale never considered that this may be the most horrific place to bring a victim of incest. It was never a nuanced idea for him to think beyond his “by the book, goody-two-shoes, idealism”. He never considered the girl, and neither did the Twin Peaks audience. Fire Walk With Me was famously rejected by audiences and critics alike, Laura’s dead body has been made into toys, Killer BOB was made into a cute popfunko figurine, and Entertainment Weekly never even bothered to cover Fire Walk With Me in their magazines celebrating the Twin Peaks revival. Laura Palmer was never taken seriously, and by extension, it feels like my own past trauma wasn’t either. The image of her screaming face hangs over me, reminding me everyday that there is no scrubbing the past out of existence, and the place of my own personal hell still exists. The posters I stared at with anxious terror are still hung up. The tv which sometimes lit the room in a flickering haze when I heard the door creak is still hung on the wall, and my father still walks this earth. The only thing keeping my own peace of mind is miles and distance, but that is not permanence. It is not reassurance. It is not sanctuary.

The final image of Twin Peaks is Laura whispering into Dale’s ear as the credits roll. It is a recreation of the first image in the black lodge all the way back when Laura whispered to Dale the first time, but it is different now. Dale is frozen in horror this time, and Laura’s face is obscured. She is not whispering “My father killed me”, but something different. Words we never hear, but can infer. “You Killed Me”, and in such, Lynch damns himself, Cooper, and the audience who never weighed the cost of what Twin Peaks coming back meant. Laura spoke, and this time she was heard.

“My mind and my life had been completely occupied by you. You came to me morning, noon, and night—especially night. That was your time, the darkness of midnight. You continually wove your spirit into my dream world, revealing bits and pieces of yourself, myself, and our fears and struggles. The thing I remember most about you, though, Laura, is your loneliness. That loneliness haunted me. Walking back into my empty hotel room by myself each day, left to deal with the fragmented pieces of my own life, your loneliness would still fill my room. My prayer is that you are now someplace where you are truly loved and at peaceful rest.”

Much love and gratitude,

Sheryl Lee

Diary entry taken from Welcome to Twin Peaks. Com. 1992

Thank you for this

Thank you. This is quite powerful. It reminds me of what I loved about Fire Walk With Me.

Let me echo my namesake's gratitude. That was as affecting as it was illuminating. Some of the best writing on Lynch – TP or otherwise – I've encountered.

Dear Willow,

I reshared this on Facebook a couple of days ago, and have been returning to it in my mind since I read it. Thank you for such a beautiful text, and one that, unlike so much writing on TP, even those that mention gendered violence in some way, really forced my eyes open to something I was not acknowledging in Twin Peaks. Much gratitude!

Perceptive, authentic, moving, illuminating and healing. Brilliant work.