|

| Ginger Snaps (2000) |

Body Talk is an ongoing series of transcribed conversations on Transgender Cinema as we prepare to write a book on the subject. This part is on the horror subgenre of “body horror”.

WILLOW MACLAY: Alyssa Heflin tweeted not too long ago upon the occasion of the release of Lukas Dhon’ts cis wet dream “Girl” that as it existed Cinematic language couldn’t tell or interpret transgender stories in a suitable way. I’ve been thinking about that a lot lately, especially as it pertains to our general thesis of “What is transgender cinema?” and I’ve come to the conclusion that I think she’s right. Transgender Cinema as it is understood by cisgender filmmakers is exterior forces and changes, but we understand transness as an internal, textural, abstract energy. Especially in the case of dysphoria. What cisgender filmmakers typically do not understand is that for us, the internal becomes external, not the other way around. Dysphoria manifests itself in real exterior ways, but it originates from an internal place. In order to accomplish something resembling a real transgender cinema cisgender filmmakers (and transgender ones too) need to work from the inside out and they shouldn’t be afraid to obscure or unsettle the image, because as trans people our experience of being alive is something that is never going to be 100% right. Of course you have to write the character with the full intentions of giving them scope and life, but transness touches everything for us, and we perceive the world in that way. This is why I think body horror is the closest thing mainstream cinema has to transgender cinema in terms of cinematic language. In body horror you get characters who are often unfairly stricken with something they had no control over until it begins to eat at them completely until they become at one with their own sickness and come to grips with their own monstrous qualities or fall by the hand of society or their own hand. The genre is rich in transgender stories, because it’s a mode of storytelling which fundamentally concerns itself with bodies, and as trans people we can never remove ourselves from the knowledge that we’re inside of our own skin. It’s always present and in body horror it’s present too, even if it is often about nightmarish monstrosities like flies, werewolves or the undead.

CADEN GARDNER: The transgender allegory found in the body horror sub-genre is connected to our own trans experiences in dysphoria, something that is not exactly predicated on time or controlled like some common pain like a headache or a head cold. It is chaotic. Cis people don’t really pick up on it, but sometimes in the most extreme cases, side effects of dysphoria are visible, be it self-harm or certain eye-catching images based on anxiety and stress. I will put myself out there and say that for years I developed a compulsion to scratch my arms in dysphoric episodes. It was not self-harm but there was a sense of helplessness from my unconscious signals about my issues- that for years I never had the courage to say out loud- were there in plain sight, until I realized I had to conceal my arms. I was embarrassed because this thing I could barely internalize any longer was starting to show itself. That trans experience is not uncommon. Have I seen that trans experience on-screen? No. I can’t say I have. Generally speaking, interiority can be difficult to convey in cinematic language but it often feels like cisgender filmmakers just see the exterior changes as a crutch and a fulcrum for the entire existence of these stories without delving deeper. There’s nothing layered in how their trans subject relate to the world, their place, and whatand how their gender dysphoria manifests itself as. In that regard, Lukas Dhont stating he wanted to make a universal experience about a trans character is immediately off. He is hardly alone in wanting to connect trans characters to some universal ideal, as that type of art seems encouraged by liberals as an antidote to reactionary conservatism. But it misses the point. Trans people have had decades of misunderstanding by cisgender filmmakers and to now go off into thinking we are all one is an incredibly insincere pivot. To course correct from decades of filmmaking that misunderstood trans people, we need to start with why we are different while grappling with no longer being an other. What does it mean to have a transgender body? We are not served that on film, so we go look to where trans people are usually conditioned to find their most common representation: the villain, the outsider, and the other.

Science fiction and horror were built from the foundation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. The monster was created from a scientist playing God and a text about a body that had no control over their reanimation. Once undead, he becomes aware of the world around him and the society that is afraid of his very existence- he hides and seeks a partner, as he is alone. Issues of identity and control of the mind and body are all there in Frankenstein and continued forward. Over time, those genres of sci-fi and horror grew and expanded into more stories and perspectives. Horrors of transforming, mutating, and deteriorating due to various forces, some of which came from within or something elusive. There was no antidote or cure in some cases, but an existential question never to be solved. The body as a vessel for chaos and the horror of that lack of control is a trans story. Not the only story, of course, but an essential text that makes up part of our narrative

|

| Frankenstein (1931) |

WM: This conversation is going to lean so heavily on dysphoria that I feel like it’s important we talk about how it manifested itself in each of us. One thing that Lukas Dhont immediately got wrong out of the gate was trying to make his film a universal experience like you said, because transness is very specific and something like dysphoria can vary from person to person in severity. For me, dysphoria was something that I immediately felt in my life. I didn’t know the word for it, but I felt ashamed of my own body because it wasn’t like other little girls and then I grew up and things got exponentially worse until I couldn’t handle it anymore. From an outsider’s eye my dysphoria probably looked like depression. I shut myself off entirely and stayed hidden in my bedroom because going out meant other people would see my body and I couldn’t deal with that, but internally it felt like my brain was poisoned. I’d punch certain parts of my body as hard as I could to the point where I’d bruise myself because I hated myself. And I’d avoid mirrors like the plague. My dysphoria has lessened tremendously over the past few years through transitioning but I still find myself hating my body and calling myself terrible names and hurting myself every now and then even today. Dysphoria lingers, even if it lessens over time. We never fully disengage ourselves from the root point of why we needed to transition in the first place. It’s something that’s just in the air of our reality.

To pull this back to cinema though, it’s going to vary from filmmaker to filmmaker in how something like body horror is expressed. We talked in the Under the Skin entryabout how science fiction and synthetic bodies grappled with questions of transness incidentally, and that’s the case here too. To my knowledge there aren’t any direct representations of transness as body horror in cinema where it’s literally about dysphoria, but there are films where girls go through puberty and turn into werewolves and hate every fucking second of it, to name one example. Something like that is close enough in my understanding of dysphoria that I can point the screen and say I recognize what that character is going through. Dysphoria is so individual and unique from person to person you’d likely get a different example from every single person you ask when you bring up the question, “what does dysphoria look like in movies?” For me, it’s that puberty is hell, but the puberty you never asked for is deadly.

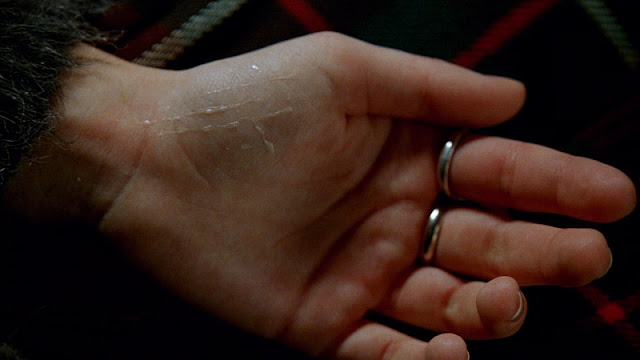

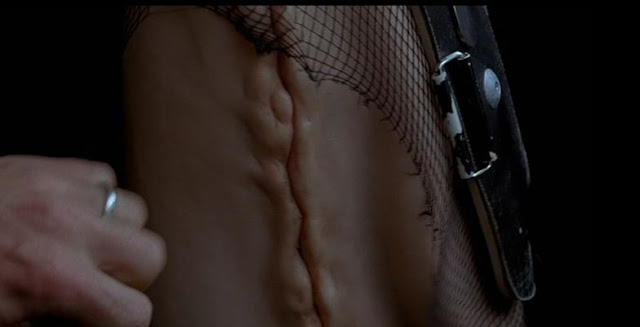

CG: You indirectly brought up Ginger Snaps and the moment that stuck out for me in that film was when Ginger (Katharine Isabelle) reveals to her sister Bridgette (Emily Perkins) her scars from the wounds she received from the werewolf. It’s not just on her chest, but the scars are growing hairs. ‘I don’t want a hairy chest!’. Ginger confides to Bridgette with absolute disgust. It is so striking. Ginger Snaps consciously builds its puberty metaphor, within the text, as menstruation is explicitly mentioned for sisters Bridgette and Ginger. I remember going through puberty and while I knew nobody would understand why, and I did not have the words, I would say this out loud, just moments of exasperation in the realm of, ‘I don’t want this!’ I can recall a parent, or a family member telling me, ‘All girls go through it’, but if you never saw yourself as a girl, well, tough luck. Pretty much every trans guy in my position can understand why that would be difficult. It just feels like such a disturbance to your body that reoccurs over and over as though to remind you of your differences, undercutting any sense of worth you might have for yourself. Ginger had a disturbance too, but in the form of a creature who attacked and bit her, but she does her best to negotiate her now fractured self (one who is now a sexually active young woman and the other who is a werewolf) but it ultimately does weigh her down. She’s been infected with something that she cannot undo and it is helpless. I can understand that and so can you.

|

| Ginger Snaps (2000) |

WM: That’s exactly it! It’s something happening to your body that you so completely reject. I’m fortunate in some sense because I’m intersex, and because of that puberty was never this thing that felt completely irreversible. I feel for anyone who is in that boat, as there are many. I didn’t have loads of body hair but what I did have felt like the end of the world. Another big moment in Ginger Snaps for me is when Ginger is trying to hide the fact that she’s grown a tail over night, and her immediate reaction is to cut it off. That scene could so easily be placed alongside a trans girl tucking, doing everything in power to get rid of this thing that’s between her legs which basically ruins her mindset 24/7. It’s the same vibe. Puberty was a fucking nightmare for me as soon as I was told about the birds and the bees and how my body would be developing. I’d become a man (editor’s note: she did not), and nothing seemed worse to me than that fate. I spiralled and everything got so much worse for me, and if we link that back to Ginger Snaps we have Ginger who is 16 and hasn’t had her period yet and after she is attacked by a werewolf she starts menstruating and turning into a lycanthrope, and once her change begins there’s no undoing the side effects. The filmmaking really taps into the bodily dysphoria and the interiority too. The hiding away in the bedrooms, the panic, the fact that the film isn’t afraid to show bodies going through change or gore. It’s all metaphorically the destruction of a body at the onset of puberty in addition to being an allegory for being a teenage girl and growing into an adult. It’s a dense movie. One I’ve always liked and one I’ve come back to again and again since figuring out why I’m attached to it in the first place.

CG: A major one for me was Brian DePalma’s Carrie. That gym shower scene, where Carrie White (Sissy Spacek) gets her period, is horrifying, grotesque and the way the other girls treat her is unbelievable. DePalma plays on how subjective that sense of shame is versus reality, putting into question how much of Carrie’s insecurities are mental versus the actual severity of the bullying she faces. Sometimes he plays too heavily into his usual artifice, but that sense of shame in feeling like a freak, however, is incredibly relatable thanks to Stephen King’s text. Everyone is laughing at her as she’s going through this change and it feels like she is being punished for something she never asked for. That was me- to the degree that my first period happened in school and well, I guess I should be happy it wasn’t in the gym showers. It might as well have been as my embarrassment from the incident painted this target on my back in much the same way. To return to the film, Carrie is othered despite her ethereal exteriority. She seems blank to the other kids, unable to really shape her own identity due to her domestic circumstances. That makes her vulnerable and innocent, but it also makes her perfect prey to attack. In the wake of her menstruation Carrie feels like the telekinesis she develops as a result is an affliction and her mother hovers over her, threatening her with eternal damnation for wanting to try to pass off as a normal girl. It goes badly. Carrie gets her revenge but has to be taken down too, because her type of story ending that way is the logical conclusion. I mean, thank God I never went to prom.

WM: I never went to prom either. Does any trans person ever truly go to prom? Realistically I think we should hold an adults prom for us only. That would be more than swell. But yeah, Carrie is this really intensely tactile film, and I can 100% understand relating to her horror at getting her first period. In that scene De Palma shoots all these other women as if it’s like this garden of nymphs, and here’s Carrie White, fundamentally different from the rest in her own mind and in theirs. It’s incidentally De Palma’s only film of consequence in terms of transness, because we both know he’s a blithering idiot on the subject. I love that one though and a lot of it has to do with the way Spacek plays the part and the way we’re foregrounded in her point of view pretty frequently. We’re asked to empathize with her, and as a trans person I think we can, because typically we are bullied, and in addition to that we’re dealing with the horrors of our own bodies in similar fashion.

|

| Carrie (1976) |

CG: Thankfully there’s a generation after ours that’s coming out and transitioning at a younger age who perhaps get to experience prom (I am sure there exists that story that makes allies happy about one school having a trans homecoming king or queen that gets passed around and shared on Facebook), although who knows if they’re in the safest, most comfortable environment in their high school. Schools have changed from my health class where transness never came up but that doesn’t correct every misunderstanding and ignorant thought about our community whether they are coming from students, teachers, or parents.

I would say before puberty I was much more gregarious and I had a very diverse friend group. Some of whom would later come out, but after puberty most of my male friends stopped talking to me. It got more polarized and gendered. I could not identify with a lot of the girls at my school and they seemed to have an idea that I was different on some level. I honestly never heard the term ‘tranny’ or any trans slur at any point in school (that may be the only benefit of the trans erasure), but they knew how to get under my skin. I was bullied and harassed, it’s not very unusual, but that doesn’t mean it somehow made the harassment and bullying feel normal or something I could escape. I had to go to school. I carried so much anxiety and pain for the fact that I knew I was different. and I could not express myself or attain any idea of who I was in my teenage years. The words eluded me and the images I could connect with were unavailable beyond internet searches that I could only get after school. Often during school I disassociated, to the point where there are no memories beyond what I have only spoken about. I was that good at disassociating. It made me become invisible and frankly, I’d rather have that than catch hell all the time.

As a result, my middle school and high school experiences were extremely interior and isolated. Some of that converged with me literally going into a room where I could be by myself. I could hide from the world. What could I do? I mean, I would watch movies but sometimes the disassociating would be so severe that I’d lock myself in spaces. Coming out of those spells was beyond difficult. I felt threatened by the outside world but what was there for me to show any sort of growth when I didn’t feel like I could express my problems? I did not watch the film until college but the Todd Haynes film [SAFE] may be the only film to convey that sense of isolation and disconnect of my body and mind, and the side effects of that. It is a body horror movie, and one that is unsettling in the sense that confronting the problem by the main character Carol White (Julianne Moore) eludes her, she can only play a part to barely survive and it is literally eating away at her.

|

| [SAFE] (1995) |

WM: I think you know my high school story, and if you don’t I’ll very briefly give you the gracenotes of an otherwise blank period in my life. When I was younger I still felt dysphoria, though I didn’t have a word for it, but not to the point where I couldn’t live my life. I could go to school, make good grades and hang out with other girls, and boys. It wasn’t a millstone tied around my neck at that point, but after puberty I started to make myself throw up before school started so I wouldn’t have to go, because I was that terrified of being seen, and it was around the time when I completely checked out. I was homeschooled after that and no one knew what was wrong with me, including myself. I didn’t know the words “transgender” or “gender dysphoria” but if I would have I could have pinpointed what was wrong with me.

During all of this time, I also isolated myself and shut the world out. The internet became my home, along with my bedroom, and our local cinema. The cinema was the only place I felt comfortable going because I was going to be shrouded in darkness. No one would see me.

When I came across the films of Chantal Akerman, and to a lesser extent Sofia Coppola, I immediately made a connection, because she’s this very interior director. She’s patient. She’ll let a shot sit for an absurd lengths so that we can feel the time, but for me, stasis felt like home. In The Meetings of Anna she frequently shoots her lead character Anna (Aurore Clement) staring out windows watching the world instead of being in it herself, and almost all of her films have moments like that among other things I’d gravitate towards. I think of Je, Tu, Il, Elleand the opening passage where Chantal sits in a room with no furniture for upwards of 40 minutes writing in a diary and eating sugar. It felt like cinema that fundamentally understood me and SAFEis an extension of that. Haynes, and much of the new queer cinema group of the early 90s, conisdering they were disciples of Chantal Akerman in a stylistic and thematic sense.

|

| Je, Tu, Il, Elle (1974) |

CG: When I was a teenager, I had some idea about the New Queer Cinema movement. There was Gregg Araki, who had just put out Mysterious Skin and I was interested in watching more Todd Haynes after coming across Far From Heaven, I’m Not There., and Velvet Goldmine. However, it was Haynes’ Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story that made me think he was a filmmaker who I wanted to follow for the rest of my life. Haynes had an understanding of what it is to be a person who was a prisoner of an identity. In the case of Karen Carpenter (recast as a Barbie doll) it was an exterior, that was effected by her internalization of the absurdly high beauty standards expected of a pop star like herself. Most notably stemming from the widely circulated, notorious comment, that the eating disorder that took her life was based from somebody calling her fat. Haynes understands his characters are on the margins of society. Some of the harshest conditions that can take control of a human body come from an exterior place, that then influence their interior selves but also reveals and informs that interior side that has long been there, unsatisfied. That is [SAFE] and for me, it hits on a trans-allegorical level even if it is something people would not immediately be drawn into perceiving.

I like that you bring up Akerman, as her film Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels is a clear influence on [SAFE]. Jeanne Dielman (Delphine Seyrig) goes through a series of routines that she must do over and over as a housewife and mother to an ungrateful son (Jan Decorte). She is framed dead-center as audiences watch her prepare meat loaf and peel potatoes in real time. Her routines wear her down and she reaches a breaking point while internalizing her feelings of unfulfilment. It ends badly with the cataclysmic breaking of routine. We feel tha due to Akerman’s patience and insistence that we watch this woman and perceive her thought process. We begin to see ennui become more visible and she’s worn down from playing by these rules that she so closely followed. [SAFE]’s Carol White never has a handle or any real ownership of herself in the same way Jeanne Dielman does, but we watch her in a similar way with a focus on her failed attempts to fall into a routine to gain some sense of self worth. But the problem with Carol White, and why I connect with her on such a deep level, is that she has no identity or really anything to claim as her own. Her home is her husband’s money, she cannot nurture her stepson because she did not give birth to him, and the domestic roles to keep the home nice are done by others because Carol’s husband has money. Her attempts at doing simple jobs like ordering a couch or just her attempting to look ultra-feminine backfire. The moment where Carol gets a perm is her cataclysmic event. Those events expose her to chemicals that reveal she is a sufferer of environmental illness, a real life illness, that is tied to her trying to assert her femininity and identity. Julianne Moore as Carol gives a full bodied performance that I still cannot shake. Her performance is criticised sometimes as being merely a cipher, but listen to her airy, high register voice that feels like it wants to leave her body. Aside from her performance there’s also intricate detail in the costuming. Look at the gauche 80s clothing that she wears, and how her wardrobe becomes washed out and blank as she gets sicker. She’s a blank slate and still unable to connect to something that can unlock her illness. She’s goes to Wrenwood, a New Age community that is all about positive affirmations but a community that avoids confronting their problems. These issues stem from their place in society. The world doesn’t know what to do with them, let alone the medical community. There isn’t a word for what they’re experiencing and their place in the world is fractured because there isn’t a language to discuss their problems. Sound familiar?

[SAFE] was made after the height of the AIDS/HIV crisis and serves as a conscious allegory of it by a queer filmmaker that correctly presented how society did treat people with AIDS/HIV at the time. If you did not die from the disease, that did not mean society understood or willing to help you. You may seek out communities but getting actual help in confronting your illness beyond positive affirmation was a serious issue. It’s something that films people want to retroactively assign an AIDS/HIV allegory miss. What could you do if you had AIDS/HIV, environmental illness, or gender dysphoria when there were no words or a dialogue happening about it? Carol White sought out empty spaces, be it an empty room, or an empty car garage. I sought an empty room in some of my dysphoric episodes too. I still do that sometimes, but I also need to have help and people to talk to rather than sink into my shell.

|

| [SAFE] |

WM: I think one of the most brilliant aspects of [SAFE] is Julianne Moore’s performance and it absolutely wouldn’t work without her full understanding of who this character is, and her place in the frame. She mentions on the Criterion Collection interview with director Todd Haynes that upon reading the script she was dying to play the character, because she immediately understood that this character didn’t want to take up space anywhere. She wanted to minimize her presence and make herself as small as possible. This ties into your comment about her voice. Notice that she’s not speaking with the full depth of her vocal chords, but merely letting words flutter out. Like she’s speaking at the top of her throat and not from her body, because there’s a disconnect between her brain and her self. Todd Haynes amplifies this by framing her in ways that reduce her physicality to the point of a small dot in the larger scope of a room or space. And we do that as trans people. We blend in, but even more than that we make ourselves invisible, especially when dysphoric. Is it a life when you flee from everything that makes life worth living? That’s a question I pretty frequently asked myself when I was a teenager, and I realize now that it wasn’t necessarily my fault for retreating in the same way Carol does in this film. I had an illness that couldn’t be treated, and damn sure wasn’t understood considering this was pre-mainstream trans presence age. I felt like if I actually spoke up about what was wrong with me I wouldn’t be believed, and I wasn’t when I eventually did talk about what was wrong with me. Carol wasn’t believed either. She was second guessed and at absolute worst even gaslighted about what she was going through in this movie. Haynes positions all of this as an AIDS allegory of sorts, but it works on multiple levels like you said, and it’s an easily identifiable film in something resembling a transgender canon even though it doesn’t directly represent transness or talk about it at all.

I think as trans people when we talk about transness we have to widen the scope of what is transgender cinema, because the literal texts so often miss the point. It’s also why queer cinema has to move beyond just what pertains to sexuality. Sexuality is important and so are stories that are literally about transgender people, but as an art form cinema can handle topics of a wider scale in different ways than direct representation. It’s intellectually dishonest to pretend otherwise.

|

| [SAFE] |

CG: Precisely. As a physical being Carol White is at the margins of her own story, the very frames of the film. She is so uncomfortable in her own skin and no matter how much she wants to assure people in her life that she is getting better, her body tells you otherwise. It is such a tough movie to watch. You’re seeing somebody never getting better because the chaos and unknown elude her. The choices she makes in trying to accept a level of culpability in being in her situation in the guise of self-help to be ‘safe’ are heartbreaking. There is a tip-off by Haynes early on that one of the few things that Carol connects to and feels like she has some level of interest in is gardening and walking around in her garden at night. She connects to nature, but a nature that contains the same chemicals that she has been advised are attacking her body. That dichotomy represents the general chaos of existing and having a body in the world. It’s quite devastating that she retreats.

To talk about queer cinema as far as dealing with bodies, the AIDS crisis did provide an interesting link in presenting a sense of dysphoria on-screen. Characters no longer had control of their bodies. To have had AIDS in the 80s was for a disturbingly long time, an unknown and widely misunderstood condition that was alienating and isolating, and society at large didn’t care. They were more ready to place blame on those with the disease for their lifestyle choices than to actually look at ways in which to help these people. That it’s still hard to this day to present AIDS in cinema as something gripping, real and a distinct period that completely reshaped the world due to conscience negligence is damning. It feels like they’ve swept it under the rug and don’t want to recognize it and stare it point blank right in the eyes. To get into other body horror films is to approach some of the films made during the time period. I mentioned how I am a bit guarded about being so insistent on assigning some of these movies as AIDS allegories, as some of them do make the host of the disease and condition that riddle through these films a complete monster, inhuman, de-personalized, and making society the victims, when that is not the AIDS story at all. But there was one that stood out for me and it is perhaps because the filmmaker had an understanding of the frailty of the human body and daringly empathized as much as one could with a person who took on such a debilitating condition. I am talking about David Cronenberg’s The Fly. In its own way and throughout his career, Cronenberg really seemed to get how much of a personal terror it is to not feel like you’re present in your own body, with your skin morphing and deteriorating in such gross, disturbing ways. Dysphoria was not as gross as a Cronenberg film to me, but boy it can feel that way.

|

| The Fly (1986) |

WM: A friend of mine once said that “Long Live the New Flesh” (the final, iconic line from Videodrome) works as both a monument to Cronenberg as a director and to his place as a filmmaker who unintentionally made a half dozen or so films that could easily be placed alongside words like “body dysphoria”, and I think that just about perfectly sums him up. I think your insistence that The Fly is his best is spot-on, even if I love quite a few of his films. Cronenberg always had a tendency towards playing in his own goop, but it’s that very essence that I think aligns him to a cinema we can understand. It’s a cinema of bodies in disarray first and foremost, almost in a state of decay from the onset with characters fighting against that feeling. It’s a kind of Canadian disposition of surviving winter and living with the cold of death hovering around everywhere, but I think it’s something we can understand fundamentally too because in a sense we have to kill our past self to bring a newer version of us into existence. We are our own ghosts and Cronenberg’s characters are of a similar disposition. But I want to hear more from you about The Fly. It’s one of my favourites and I’ll get to it in a second, but I’d like to hear you elaborate first.

CG: What I like about Cronenberg is that there are, as you said, bodies in complete disarray and characters grappling with various levels of control with their bodies. Some of these characters know and have a certain level of agency over how they are treating themselves that is mostly out of step with society’s norms. There’s a sense of reckless abandonment, like Videodrome, in being so disconnected and seeking out something more experiential than what society is giving you, but I don’t sense a moralist streak in Cronenberg. It’s quite queer, and Crash is the best example of that sense of bucking society’s norms on a sexual and identity level played in hypertext. But to hit on The Fly, Cronenberg’s more mainstream and major studio works showed more of a relationship to normative society existing around these characters. The earlier works, Shivers, Rabid, Scanners, and Videodrome are still playing within a level of their own logic that the audience is dropped into and needs to be acclimated to rather than our common, normative world setting the rules. Cronenberg’s remake of the Kurt Neumann’s The Fly from the 1950s has its entry point be Geena Davis’ Veronica ‘Ronnie’ Quaife following and then engaging in a relationship with Jeff Goldblum’s Seth Brundle. Brundle is cast immediately as an eccentric and somebody who wants to please Veronica by having his work impress her. He’s insecure and it clouds his judgment, his experiment on teleportation becomes tainted, that then leads him to take on the characteristics of a fly. It is a deterioration that is quite devastating but initially Seth’s results show that he becomes an ideal partner to Veronica on a physical level, and he credits his teleportation. But his changes become more negative, violent, and averse, he transforms into a monster, but even before he goes full-blown monster, he ceases to be the man that Veronica once knew, and was in love with. He is dehumanized and has his humanity removed. That does not mean Veronica completely recoils and rejects him despite gaining her own trauma due to the fact that she gets impregnated by him and has nightmares of giving birth to a creature (probably the biggest connection to the AIDS allegory is the fear and anxiety of having a condition transmitted sexually). She wants to care for him and save Seth but does not know how, but does grants Seth his wish of being shot with a gun to kill him and end his misery. The deteriorating body that isolates and alienates, a monstrous sight at a man who wanted to play God and self-improve in order to be somebody more than an eccentric nerd. That’s how I see The Fly. The idea of trying and it turns into a self-inflicted wound, a cause for more disarray, chaos, and dysphoria in the body. You look like shit and you cannot really seek help for that.

|

| Crash (1996) |

|

| Rabid (1977) |

WM: I think the idea of playing god is also present in our general makeup which also makes The Flymore resonant. What could possibly be more like playing god than changing your entire body and some pre-supposed destiny into something entirely different? Brundle dies for this, but what essentially separates itself from other tragic martyr tropes is that the film is never played for it’s melodramatic reveal. It never unlatches itself from its own DNA in horror and because the film is ambivalent in a moral sense I don’t think Cronenberg asks us to weep for Brundle even if we may. In a narrative context his failed science experiment is not inherently different from the people who died transitioning when surgeries were brand new and doctors didn’t know what they could and couldn’t do. It’s an Icarus syndrome and it’s inherent in us.

Jeff Goldblum and Geena Davis do a lot of the heavy lifting in terms of getting across the internal scars of what’s happening between them. Geena is the onlooker not understanding what’s happening to this person she had initially fallen for while Goldblum has to grapple with his body becoming inhuman. Goldblum spends a lot of time in mirrors staring at his rotting flesh while the work of brilliant special effects artist Chris Walas, does its job in getting across how horrific he views his external self while his soul is still clamouring for the life he once had. He doesn’t immediately shut down and decide to die, but it’s a slow, agonizing process where there’s nothing left. He accepts his death, because he lets who he is drift off to sea, never to be seen again. You can’t be a human if you’re so different from everyone else that no one else can understand, and that’s lateral to our issues as transgender people.

Even beyond The Fly I think Cronenberg has a rich visual catalogue of images that feel blatantly transsexual, even if they don’t have further context. I think of James Woods, shirtless, appearing to be a man in all ways, except for the cleft that resembles a vulva on his chest in Videodrome. He panicks, reaches in and finds a gun. Is that a suicide image? His own latent anxiety at what’s happening and his mind summoning a gun? One could argue. There’s also the image of Roy Scheider in Naked Lunch revealing himself to be living underneath the skin of a very normal looking cis woman only to be a bare chested, hairy son of a gun with a cigar in his mouth. That one’s more punk rock. But I think of these images, often, and there’s certainly more than those two.

|

| Naked Lunch (1991) |

|

| Videodrome (1983) |

CG: That image in Naked Lunch is incredible. I recall Cronenberg saying that he

believes everyone has control, with varying degrees of complete grip, over

their identities. This makes sense to me. He is not really casting a judgmental eye but showing people going through self-discovery that it can sometimes be trial and error, wear and tear, and can doom them, but that is more Cronenberg presenting human fallibility than damnation. And his stories make sense as far as seeing these bodies in disarray and these choices being made because Cronenberg’s worlds make sense. The images are surreal, subversive, but the characters are very real, sometimes even operating in very traditional film archetypes. But of course there is a level of transgressiveness in his work that makes his films challenging for people. He knows his characters are not normal based on the rules and understanding of modern society but there is no dictating of norms and rules within his work. That makes his films extremely easy and freeing to watch as a trans person. Even his most classically made work, A Dangerous Method, a play adaptation that’s based on the real life psychoanalysts in Carl Jung, Sigmund Freud, and Sabina Spielrein, offers something for me as a trans person through Keira Knightley’s deeply rich, and extremely misunderstood, performance of Spielrein. It’s a full bodied performance, incredibly physical, unhinged jaws and body contortions that make her feel diametrically opposed to Julianne Moore’s Carol White. But Spielrein goes from a patient, considered emotionally unstable, to somebody who confronts her trauma of her past life and is able to finds words of what has eaten away at her. She improves and takes an interest in psychology, becoming a student and then ultimately, one of the first female psychoanalysts. It’s so simple and may be shrugged off as spotlighting a simple feminist strain of a major figure in her field, but I find that Cronenberg shows amid the disarray of his characters and their bodies, there can be a confrontation with the problem and that can be tied to an identity, a trauma, something that had been elusive and hard to explain and that can lead to finding peace. Spielrein in A Dangerous Method is a body horror story, that includes a confrontation in the form of BDSM in her sessions with Jung, that can have a happy ending (well, happy to the extent of Spielrein’s success as her real-life had its own unfortunate end due to being a Jew, her religious identity used against her, in World War II).

WM: The most interesting thing to me in A Dangerous Method is Keira’s performance. It’s full body acting and unleashes a kind of torrent inside of her in terms of the physical horrors she’s manifesting through acting. It’s a great performance and everything that Cronenberg does with Body Horror, but on a theoretical level instead of one reliant upon special effects. All the terror is completely inside of Knightly’s own process.

|

| A Dangerous Method (2011) |

WM CONT: You mention the word “trauma” above and I want to get into that a little too, specifically the works of a handful of actors and directors. This isn’t necessarily connected to transgender cinema literally either, but in the ways these things can intersect. Rob Zombie’s films really hammer things home for me in this regard, and I’ve written about them extensively. In The Lords of SalemSherri Moon Zombie plays a woman who is essentially cursed, a daughter of Salem unfairly brought into a centuries old blood pact which leads her to spiral into a mess of trauma, relapsed drug use and hallucinations. Hallucinations in particular are what I want to gravitate towards, because they take the real world and make it strange, and I think that’s how we perceive things, even if it isn’t as loudly stated as bugs ripping into your flesh or vomiting black sludge. The main point is that something is amiss and dysphoria can tangle the world into a poisonous vine of self destruction. This abstracted imagery due to trauma is also strongly present in movies like Jack Garfein’s “Something Wild”, the filmography of David Lynch and in the work of Hideaki Anno’s epochal, Neon Genesis Evangelion.

|

| Neon Genesis Evangelion |

CG: Part of being trans and then telling people about it is how seriously they take you. A lot of that can result in years of internalization for fear of being misunderstood and not taken seriously at all. Telling someone you’re trans shifts their image of you, and that can take its own toll on us, because we have no idea how someone is going to react. If you have no trans health providers or health insurance or find yourself isolated, what can you do? Even with those privileges that I have had, in my period of not being able to tell anyone, I disassociated which has me operating with just periods of my life that are blank for myself despite people recalling me in an image that I was disconnected from in those timeframes. That disassociation came as a reaction to trauma and torment in addition to dysphoria that festered into just more inner-turmoil. When I got older, I was self-medicating my problem, even as I was becoming increasingly aware that I was trans, by drinking alcohol. I am a recovering alcoholic. I am upfront about it because at this point I feel like I have nothing to hide. And I feel like, unfortunately, based on the numbers and studies of trans employment, suicide rates, uninsured, and other surveys done, that we are not really alone in having traumas in addition to our gender dysphoria. I can see a film about an alcoholic or even somebody feeling like their memory has been manipulated in a way where I see a film on trauma and disassociation and connect with those works. I echo your sentiments on the films of David Lynch, Garfein’s Something Wild and would include Lynne Ramsay’s recent You Were Never Really Here as well as Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight as far as achieving trauma, disassociation, and feeling off-centered. That feels right at home for me.

Films gravitating toward body horror that understand the frailties and fallibility of the human body, feel like the closest depiction to our issues I can imagine on-screen even if it isn’t direct text, just shrouded in allegory. Cronenberg did to a trans film called M. Butterfly but that is Cronenberg’s worst film because it betrays a lot of what makes him great. The trans character of Song Liling (based on the real-life opera singer turned spy Shi Pei Pu that “fooled” a French diplomat in identifying as a woman when was just a male performer posing as a woman) just feels at such a distance and enigma who is never interrogated and has that eye-roller of a scene where John Lone strips naked of his character’s ‘true self’ as revelation. That film is perhaps more of a failure of the pre-existing text of the widely known David Henry Hwang play, but it is quite ironic that Cronenberg’s allegories that you can connect to transness feel easier to connect with as a viewer than his film about an actual trans person. That was somehow between Naked Lunch and Crash. I felt like I had a better idea and grasp of the characters turned on by being in car crashes than a trans character ‘pretending’.

WM: I feel you in a major way. It’s true that telling people you’re trans automatically alters that image of you. It’s like a small death, and it’s on us, perhaps unfairly, to reaffirm to that person that this other thing is the real version of ourselves. It all comes back to images doesn’t it? How we view ourselves. How we’re perceived by others. No wonder we’re so obsessed with cinema considering the image is everything. What is so stirring about body horror is that through it’s broad abstracted images on the human body in a state of disarray it somehow comes close to touching on something resembling cinematic language that is actually functional with transness. Melding body horror into realistic human drama is perhaps how to achieve a true transgender cinema. Something that I don’t think I’ve ever seen in fiction filmmaking. We’ll chase that and keep creating until it exists, and we’ll keep talking about it. Talking about transenss and getting it out in the open is why we, as a community, have made strides so far in the past five or six years, and that’s no small feat in and of itself. Maybe a transgender cinema can exist.

|

| Inland Empire (2006) |

Be First to Comment