Ray Liotta never planned on becoming an actor. When he was in high school he was a classic jock and took pride in the fact that he was on a number of athletic teams. He didn’t even really want to go to college, but wound up at the University of Miami. In his own words, “they’d take anybody back then”. When he was looking to sign up for classes he wanted to avoid math and science at all costs. He had a mentality where if he didn’t want to do something he simply wouldn’t, and he figured it was an easy enough way to avoid those classes if he took on acting and performing in the theater.He had some urging from a fellow alumni who approached him on the day they signed up for classes. She was cute so he followed her over there, and in doing so, he found his calling. He was thrown into the deep end and almost immediately began participating in musical productions of Oklahoma and Cabaret. He didn’t have any butterflies about performing, because he didn’t believe he could really make a fool of himself if no one really knew him. With a clean slate he took on this brand new interest of his and found that he loved it. He was off to New York not long after schooling and was set up with an acting teacher by the name of Harry Mastrogeorge, who he returned to periodically throughout his life, and taught him a valuable lesson: “never lose touch with the part of you that pretends”. Mastrogeorge believed that acting was like a muscle that needed working out, and he also believed that anyone could be an actor, because as children we always took on new roles with our imagination. Under Mastrogeorge, Liotta found someone he could really trust and in that union he felt as though he was able to unlock his abilities. It was never a method experience for Liotta, but something very nearly pure about expressing yourself, and that was the effect that Mastrogeorge had on the young actor. He studied like any actor would, but time and time again Liotta would return to Mastrogeorge throughout his life to stay in touch with the part of himself that allowed him to pretend.

In the early 80s Liotta spent three years working on the soap opera Another World, which is where he cut his teeth on screen-acting, and it forced him to get better at memorizing pages of dialogue, and acting on the fly. It was a good gig for a young actor all things considered, but after three years he decided he was going to try his hand at the movies, and he very nearly quit acting during that time-frame. But as luck would have it Liotta was longtime friends with Melanie Griffith (she introduced him to Mastrogeorge), and she had some say in who was going to play Ray Sinclair in Jonathan Demme’s next picture Something Wild (1986). Griffith had a bad experience on set some time in the past and Demme wanted her to be as comfortable as possible. Her role was one where her character was going to experience abuse at the hands of Sinclair. Liotta heard about his friend undertaking this new project, and he initially didn’t want to call her and force his way into the casting room, but after some urging from his parents he made the phone call. A light bulb went off for Griffith, who felt that Liotta would be right for the part, and Demme gave the young actor a shot. He got the gig, and when watching the movie it isn’t difficult to understand why.

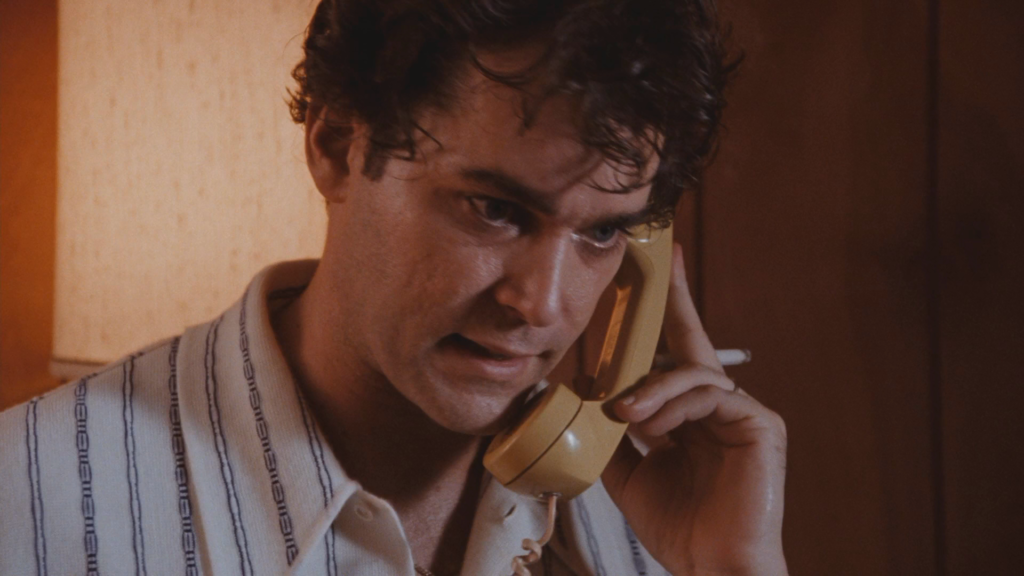

Initially Something Wild almost feels like the Preston Sturges screwball flick The Lady Eve (1941). Charlie Driggs (Jeff Daniels) is a by the book investment banker in New York City, and he is the dweebiest of the dweebs. You can’t say the same for Audrey (Griffith)who blows into his life like a hurricane force-wind of cool with her Louise Brooks bob and Madonna accessories that any stellar chick in the 80s would’ve had. It’s a bit of a laugh for her to drag Charlie around by his dick, but in the process she falls a bit for the guy. He’s not at all like her “ex” and showing this wallflower how much fun life can be is a rush in its own way. They end up at her high-school reunion, posing as newly-weds, and this fun, if vapid, comedy is completely annihilated with the arrival of Sinclair. With Liotta’s performance, and the structural shift that Demme places in his hands, a good movie becomes a great one. As Demme is wont to do, the band performing at the high-school reunion is The Feelies, and Sinclair is introduced alongside their song “Loveless Love”. With a minor, jangling riff and the lights down low everyone slow-dances, but the vibe is off. It’s not a song you really slow dance to. Demme always communicated through music, and with this song he gives Ray an air of menace, but the brilliance of his introduction is the casualness in how he displays a level of control over Audrey. It doesn’t take a lot to tilt the film sideways when Liotta’s character is introduced, and the way he slides into frame with another girl, slow-dancing, and presses up against Audrey, who cannot see him, is destabilizing. Then with a chilly voice he says softly, “hey Audrey”. The Lady Eve vanishes with those two words.

The second half of Something Wild is dictated by Ray, and Liotta makes numerous choices with the character that are curious in the larger context of characters who are abusive. It would have been very rote if this character were only a brute, but he’s very boyish and playful. It’s those secondary qualities that allow the viewer to understand why Audrey ended up with him in the first place, because she just spent the past hour taking Charlie on an adventure he never considered. He also has a sexuality that is easily discernible. Even with the red flags going off in that scene with The Feelies there’s something seductive about the way that Ray carries himself and gets what he wants. It’s that bad boy thing, but made precious because Liotta chooses to be playful rather than coarse. It makes the abuse that much harder to watch as well, because Liotta is presenting more than one trait at a time, which gives it much more power as a statement on relationship dynamics. If Ray is left to his own devices he’ll never change, because he’s stunted, territorial, and frustrated, but he also knows exactly what he’s doing. Life is his little playground. Even when Ray ends up with a knife in his guts he recoils with the words “shit, Charlie”, as if he were about to say he was just messing about. It was all a game, and Liotta has this beautiful close-up of pure shock in the wake of his character’s looming death. Pauline Kael once wrote of Demme that while watching his films it’s easy to get the sense that if the camera were to abandon the main plot and chase the goings-on of an extra it would still make for a great picture. Ray is the clearest indication of that idea. Something Wild is two pictures and one of those belongs to Ray Liotta. Most actors would kill to have Something Wild on their resume, because all it takes is one great performance for an actor to live on forever, but Ray Liotta had two.

“As far back as I can remember I always wanted to be a gangster.”

There was a buzz around Goodfellas during its production cycle, and every actor in town wanted to be considered for the role of mob rat Henry Hill in Martin Scorsese’s newest endeavor. For a long time Tom Cruise was considered the front-runner, but that luckily never came to pass. Scorsese had seen Jonathan Demme’s latest film Something Wild, and he thought Ray Liotta was quite excellent, but he hadn’t really seriously considered him for the role until he met him at Cannes where his controversial The Last Temptation of Christ (1987) was set to play. During that period Scorsese was flocked by security guards, because he was getting death threats, but Liotta paid little attention to this, and approached the director anyway with the intention of discussing his interest in the role. The security guards moved towards him, rushing the actor, but Liotta had a presence, and he held his ground, de-escalating the situation quickly, and making it clear that he was no threat. Scorsese was impressed by the way he handled himself and believed that Liotta understood how to navigate a potentially violent situation with relative ease. He wouldn’t have to explain any of that to Liotta, because he already knew, and in that moment Scorsese had his Henry Hill.

Henry Hill was the role that Ray Liotta was born to play. Things begin in-medias-res. New York, 1970. There’s a dead body in the trunk of Henry Hill’s car and he, the hot-headed Tommy (Joe Pesci), and his mentor Jimmy (Robert De Niro), are off to bury it in some misbegotten, rotten place upstate. It’s one of the only scenes in the picture that takes place in real time, because the rest is nostalgic, lifted to the heavenly place of a dream come true through the perspective of Henry. In voice-over the first thing he ever tells us is “all he ever wanted to be was a gangster”. He loves this shit, and Liotta speaks with soft clarity and a reserved, giddy warmth at his memories living the dream. Much of Goodfellas is built around Liotta’s work in voice-over and the brilliant structuring of editor Thelma Schoonmaker and Scorsese’s near constant use of montage. Goodfellas is remembered as one of the greats of its era, because it moves so very well, and it is all in lock-step with Liotta’s work. In Something Wild he played Ray Sinclair with a boyishness and that is translated in his performance as Henry with subtler notes. When the film moves back to 1955 and he starts talking about his adolescence he sounds like a boy talking up his heroes, and there isn’t a single pang of regret. It’s important in his depiction that he not moralize his own experiences as a gangster, and Liotta makes the choice to coat all the details in a glowing amber of adoration. His Henry isn’t in the least bit ashamed of becoming a gangster, because he thinks it’s the coolest thing in the world, and the subjectivity of the picture demands we think of these things the way that Henry does. In these earliest voice-over recordings he might as well be a kid who loves baseball getting to suit up for the Yankees.

Henry Hill as a gangster is to men what Audrey Hepburn in the finest Tiffany jewels is to women. The central appeal of both performances is elegance and how smooth life might seem when you’re truly one of the beautiful people. After the flashback sequences to Henry’s youth are concluded Scorsese gives Liotta an unreal star-making shot that’s usually reserved for actresses in movies older than this one. He tracks his camera up from Henry’s snake-skin loafers, and along his shining silk suit, tailored to perfection, and Liotta looks like a matinee idol, or maybe a male-model who got their character by getting into fights. He’s gorgeous, his image decadent, and the way he leans on the hood of his car with a cigarette in his mouth is unbelievably sexy. This is the image of the gangster that Henry projects, and make no-mistake about it, it is an image, and a put-on, but looking at him you’d think there was never a gangster in pictures before, because he’s so definitive.

Scorsese gets a lot of credit for the tracking shot where Henry takes his new girlfriend Karen (Lorraine Bracco, who is fantastic) to the Copacabana and skips the line entirely, but a big reason why that scene works as well as it does is due to Liotta. When Henry speaks of his infatuation with the lifestyle of gangsters he’s really talking about power, and the ability to wield it with such ease. When Henry walks into the guts of the club he doesn’t just take Karen inside, but makes a habit of interacting with nearly everyone he comes across while stuffing money down their pockets and carrying on with small talk. Henry laughs every now and then – it’s a tic with this character – and he moves through the hallways and kitchens as if he’s pre-ordained to inhabit these spaces and rub elbows with these people. He’s in no rush, because the world is his, and getting what he wants is as natural to him as breathing. He’s comfortable and fits into Henry with an organic quality of no distance between performer and character. All the while he’s got his arm around Karen’s waist guiding her through this world of power, and she’s overwhelmed, and smiling ear to ear. She’s never felt that special. She could get used to this. It’s a fantasy and Scorsese’s virtuosic camera treats it as such. If Henry doesn’t have to worry about roadblocks then neither does Scorsese. To use a cut here would be to disrupt the constellation of Henry’s privileges and break the spell. And likewise Liotta never insinuates that Henry would ever run into any trouble in his entire life, because Henry never assumed he would. He’s a gangster. The world is made for guys like him.

It’s that exact belief that gets Henry in trouble, but it also gives the film, and Liotta’s performance tension. While watching Liotta you get the sense that his own displacement with identity unconsciously informed his role as Henry Hill. Liotta was adopted, and unsure about his genealogy, which he talked about frequently in interviews in the previous decade. He was not a method actor, but it’s possible that he and Henry had a kinship with one another. There is a cognizant realization that Henry isn’t quite one of the guys. It’s important to remember that he said he “wanted” to be a gangster and not that he was one by default. There’s some costuming happening with Henry that Liotta taps into via fidgeting in tense situations. He’s an actor who uses his entire body and his emotions tend to run down the veins of his arms and into his hands. There’s also a nervous, de-escalating laugh that becomes a primary character trait of Henry’s that is used exceptionally well in the scene where Tommy asks him why he’s “so funny”. Pesci always seems to play characters who need to learn breathing exercises, and his Tommy is particularly violent and frustrated with anyone who might perceive him as lesser. He’s a classic short-man character who over-compensates with violence and follows in the footsteps of actors like Edward G. Robinson, who was as definitive a gangster as anyone. The “funny” scene comes early on, which is important, because it stresses to the viewer that Tommy is violent, and Henry will never be one of the guys. Not 100%. There’s a near constant awareness needed with a part like Henry where he needs to project his own image of a gangster to not be found out, because he wasn’t born into that world, but worked his way in. This means that Liotta is almost never allowed any privacy to show us the “real” Henry, so the assumption must be one of transformation. It’s telling that some of Scorsese’s first images of Henry are that of a wide-eyed child staring out a window at a gangster hang-out. Henry never loses those rose-coloured glasses, not even when he’s behind bars, and Scorsese doesn’t either. He and Liotta are completely in sync with one another, but every now and then there’s some panic about being found out. “How am I funny? Do I amuse you?” comes out like a blade for Pesci, and in contrast, “I just think you’re funny” is meek, vulnerable, and worried for Liotta. It’s one of the only times Henry is scared, but he’s not afraid of death. He’s worried about the dream ending. He’s just a boy let loose as a man in this world of violence that he so admired. He looks up to all these guys, which means he’ll never be a gangster in the way that they’re gangsters.

Henry is a glamorous, high-rolling mobster of affluence until he goes to jail and picks up a coke habit. Fresh out of the joint and he’s already lost some of the trust his guys had in him, because they can see all over him that he’s becoming jittery by the day, and his drug expenditures are a liability. Jimmy sticks to what he knows robbing money from the air-lines, and Tommy keeps sticking his gun where it shouldn’t belong, but deep down he probably knows he’s getting gunned down someday. Henry though….Henry is up the creek without a paddle and it all collapses for him with the visit of a wandering helicopter. It’s one of Scorsese’s best moments as a director and Liotta’s as an actor. Henry’s got a busy fucking day ahead of him. He has to sell some illegal firearms, pick up some dope for a big drop off, take a cousin of his home for a family gathering and cook his signature pasta sauce for the family. It’s a lot. He’s going to need a hell of a lot of coke to get through the day.

After Henry picks up his drug problem Liotta shifts the way he acts in subtle ways that become more and more pronounced as the film moves along. It isn’t the typical characterization you get with someone abusing drugs where they become grotesque overnight. It’s numerous smaller choices that inform a whole. He looks around more often. He grabs the back of his neck during conversations. His eyes are open just a bit wider. The hair and make-up crew do an excellent job of making him and wife Karen, who is also using, look just a little less clean than they should. If you compare this Henry to the same one in that tracking shot his invincibility is gone along with his sense of ease. Liotta’s physical acting was previously smooth, and he was gliding along with Scorsese’s camera. During the helicopter sequence the editing picks up speed, there’s some axial-cutting to get from task to task, and through all of it Liotta is acting with a tension that was previously unheard of for this character. This is most apparent in his eyes. Liotta’s eyes are his greatest asset as a screen actor. They’re cobalt blue, piercing, and command the attention of the camera. Being paranoid and on cocaine means a lot of rapid eye movement, which he doesn’t over-do. Instead of being hyper, his eyes look worn out, squinting and harried. When the cops finally pull a gun on him and end his fairy-tale for good Scorsese gives Liotta a close-up and trusts those eyes of his. The expression on his face is muted, numb, with echoes of both frustration and relief. The jig is up. He’s a gangster no more. Liotta doesn’t blink in the long close-up. Henry sits there in the death of his own identity, and Liotta gives us a complicated, hard to read reaction. Henry is frozen in that moment perhaps for the rest of his life.

Ray Liotta’s legacy will always be tied to these two performances, and when he passed away recently my mind immediately went to his work as Henry Hill in Goodfellas. It is special. He never had a role as good as that one ever again, but he was an actor who was always challenging himself, and attempting to learn. Even late in life he gave us the best performance in Noah Baumbach’s Marriage Story (2018) among incredibly gifted talent like Adam Driver and Laura Dern. He was an exceptionally precise physical actor, but he never tied his physicality into broad, obvious transformation, like many of his peers. He never took acting so seriously that he became overbearing in his craft, and he often put in good work, because he was in touch with the imagination of acting. He was completely unique during his era of American cinema and the movies are worse off without him and the way he approached acting.

“It wasn’t some crazy thing. If I stuck to playing pretend I couldn’t go wrong.”

-Ray Liotta, 2018

All anecdotal information in this essay was taken from the following sources:

Ray Liotta Interview with Empire Magazine

GQ’s Oral History of Goodfellas

Ray Liotta discusses his career

Pauline Kael review of Something Wild

Be First to Comment