Watching old movies was the only “normal” thing about the past year.

Chick Strand’s Soft Fiction is the rare film that both clarified my own philosophy of what I want out of cinema and expanded my own vocabulary of what cinema could be. Strand’s camerawork is interested in a call and response effect of story-telling through the extreme close-ups of her female myth-makers and then commenting on those stories through images that are grounded in the bodies of women. Soft Fiction tells you what it is in the title as a simile for women’s stories, but the beauty in Strand’s work is in how she shows you the ways women move through the world. With her camera she fixates on the bodies of women, in kitchens, on streets, in bedrooms and absorbing the sun.

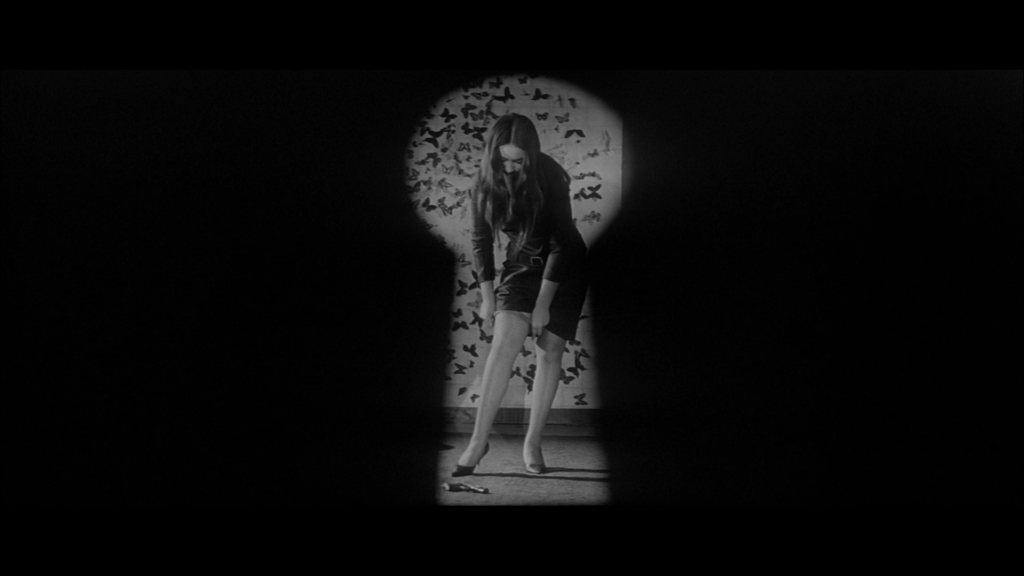

Earlier this year I watched Scout Tafoya’s video essay on Cinematic Womb Spaces, which included the scene from The Conformist that is pictured above. Afterward I couldn’t get the image out of my head and its eroticism and the complicated renderings of its context would not let go of me. I doubt it ever will. Giulia (Stefania Sandreli) recounts her first experience with sex when she was a young girl to her then lover Marcello (Jean-Louis Trintignat), and with her narration of these events Marcello replicates the past with his touch, but in a new context of eroticism instead of Giulia’s initial experience of abuse. This is deeply complicated work, and Sandreli moves through an entire palette of emotion and release with her body. In a movie that is functionally about the ways people can find themselves bending to fascism this scene is utterly liberating in its conceit and what it projects with Vittorio Storaro’s cinematography, Sandreli’s acting and the choreography of their bodies in a budding ecstasy that is dripping with melancholy and then heat.

Floating in the clouds with Rock Hudson and Dorothy Malone as they talk about what they have and what they don’t in the endless night of an effortless conversation.

In the Winter of 2019 my husband and I decided to embark on a project to watch all of Akira Kurosawa’s movies. Among those that I had never seen before High and Low was the best. This is Kurosawa at his most daring on a level of staging and straight-forward impactful imagery. High and Low, like The Bad Sleep Well (1959) seems to predict the cinema of the future, but where Bad Sleep Well feels as if it summons the work of Francis Ford Coppola, Roman Polanski and Martin Scorsese into focus, High and Low does so for autuers like Bong Joon-Ho with blunt class consciousness and David Fincher with procedural nuts and bolts of an investigation that is salacious and thrilling. When Kurosawa finally trudges into hell and creates his “Low” from the title it is transgressive, dirty and around the corners you’re not supposed to turn. These slum worlds were rarely given the space to exist in Japanese cinema prior, but after Kurosawa, the Japanese New Wave would dwell in them forever-more as cinema collapsed in Japan and transformed into a den of sex, blood, and bad taste in the early 1970s . Kurosawa’s High and Low would see the future, for better or for worse. Toshiro Mifune’s face in those final moments seems to know this too. A storm was coming.

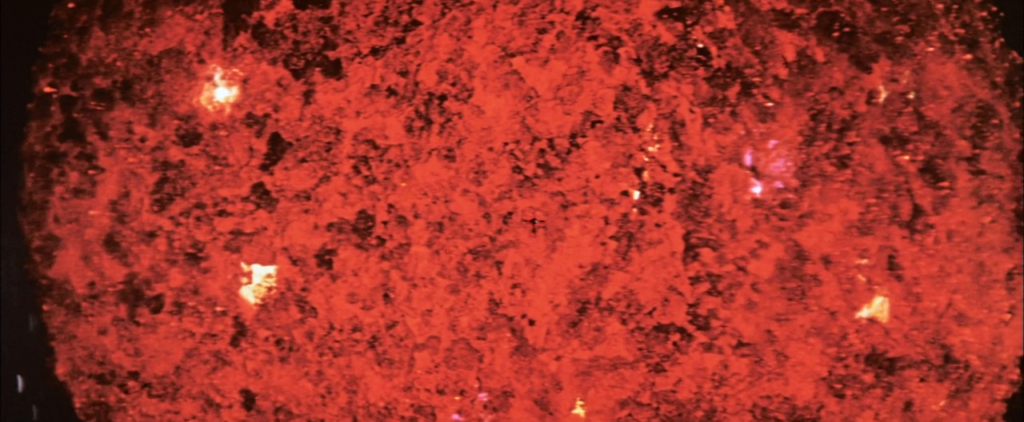

Belladonna of Sadness was singular at the time of its release in 1973 and addressed historical misogyny in the ways that it can compromise or in some cases annihilate the bodies of women. Rendered through beautiful watercolour paintings, much of Belladonna is brought to life through the close-ups of lead character Jeanne, and many times her tragic face resembles the complicated emotions of Lilian Gish, when she was working almost exclusively as D.W. Griffith’s tragic martyr. This story of extreme misogyny and violence does not make the implication that Jeanne is a universal figure for all women, but does present her in a not too dissimilar way from the biblical Eve. She has more in common with the tempting snake than the average woman, but the fatalism of her story, and the way it is rendered through oozing, wretched, red and black paint and a gaze of furious intent, does contain within an elemental anguish at those who attempt to fracture the psyche of women everywhere.

Bette Davis has never been more subtle or reserved than she was in Now, Voyager. This is a performance that expands the common idea of Davis into a more rounded whole. Everyone knows that Davis has an emotional valve that can stretch intensity into a state of hysteric animation, but in Now, Voyager her work isn’t as pronounced or deliberate. Take the image above, where Davis’s Charlotte Vale is re-introducing herself into common society after years of suffering abuse from her mother. Vale is a stunted woman, like many of Davis’s characters, but with Vale she cannot come at her emotions from a place of arrogance. She is unsure of herself, her eyes are glassy, and she refuses to make eye-contact. Her outfit is loud, but in an over-compensating way to act as a shield. The wide brim of her hat and the veil that hangs underneath announces itself so her face can become secondary, but through all of this Davis must act this role with the knowledge that it is a vehicle for her acting abilities. Rapper is not going to paint with his camera in the way someone like William Wyler would, so her acting must be that much more captivating, and it is with her Charlotte Vale that she creates the entire movie in the roadmaps of the emotions that you can trace on her face. As is constant with Davis, it is easy to understand and comprehend where her character is coming from and how she uses her technique to relay the emotional context of any given moment, but I love Now, Voyager, because it is a challenge for Davis to characterize herself in meekness while still giving a performance that’s a little bigger than everyday life.

A strange film of jagged edges, dead-ends and sickening moments that act as a buried mine going off in the form of Samuel Fuller’s no-nonsense image making. The Naked Kiss takes the moral center of Mom and Pop Mid-Western American values and curdles them under the weight of truly salacious material involving childhood sexual abuse and the political machinations that protect such monsters. But Fuller only moralizes through his choices of image like that of Constance Towers’s face as she realizes what she has stumbled upon or that of a child skipping through a house, whose long shadows evoke something displaced or sinister. The Naked Kiss is undergoing something akin to constant reinvention and never settles into the formula of a typical film Noir and because of that it becomes all the more destabilizing and uncomfortable to witness everything come to light. This is a movie you’re glad to be through with when it’s over.

Esther Regelson’s relatively unknown WMEN is the finest example of transgender cinema that I watched in 2020. Shot in gorgeous 16mm Regelson’s film suggests a literal shapeshifting from female to male or something inbetween through the sheer force of will that can come through gender expression and presentation. A leather jacket and a handful of grease is applied to the hair of our hero as they are soundtracked to an old Beatles diss track “Are You a Boy or Are You a Girl?”, meant to ridicule the world’s most popular rock band as a bunch of Nancies because their hair was a bit long in the 1960s. All of these choices are in communication with one another and evoke a sense of gender euphoria through self-determination. This is liberating because it exists outside of medical intervention and suggests something far more internal, expressive and personal. Gender can be whatever you make it.

Woman in the Dunes is a Rorschach blot where the central metaphor of shoveling sand day in and day out so that it may not overwhelm the homestead could mean anything. What is more deliberate and far more captivating is the texture of how this story is told and how that lends itself to the human body and the sensuality that comes when we exist in a state of pure nature. Hiroshi Teshigahara’s form is droning and deliberately fragmented. He takes his time to show the curves and sloping layers of skin, caked in sand, of his actors; building to an unforgettable sex scene, where all the tactile imagery that preceded is reintroduced as a flowing river of human secretion and ejaculation.

Cheh Chang made a few films about the destruction of the Shaolin Temple, but this one may be my favourite. Shot with a bevy of beautiful outdoor vistas and a priority on training and then attention paid to the counter-attack of initial violence this is another Shaw Bros. joint that is sneakily pacifist in nature, but that doesn’t mean that the final reel where all the action culminates isn’t completely fucking awesome. You could always trust in Cheh Chang for that sort of thing.

Nellie Killian’s “Tell Me: Women Filmmakers, Women’s Stories” series, which was added to the Criterion Channel, is well represented on this list, and by far the best curatorial work I came across last year. Betty Tells Her Story is a play on structure: the fable of the perfect dress, told twice, in interview form. The fascinating aspect is how the story evolves, even with little time inbetween, as something melancholic and liberating depending on perspective. Brandon’s camera is essentially locked-in, there’s little in the way of a cut, so if the film is to have a definitive aspect about it then it is through performance, story-telling, and structure. Betty Tells Her Story has all those qualities in spades.

I’m a girl who likes white horses, and they seem to follow me around from time to time in favourite movies of mine like Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me and Rob Zombie’s Halloween 2. The Wind is another. Sjostrom and star Lilian Gish are perfect for one another. With Griffith Gish was forced into a type of singular acting, and while she was phenomenal at playing those women for whom death was only a breath away, she was freed when working with Sjostrom. In The Wind Gish creates a blue-print that every actress in the horror genre would follow. With the barrelling, heaving, howl of nature’s fury outside her door Gish is given a bevy of close-ups to look back with eyes that lacerate in response. Granted, she still does plenty of screaming and suffers in her own right, because cinema loves a woman in trouble, but in The Wind she has a survivor’s streak and a physicality of floating, theatrical gestures that play to the back of the aisle that don’t seem so small when placed up against something as existential as the blustering gale of evil men.

Varda’s work always sought out to capture the beauty and diversity in the human face and her short film which observes the Black Panthers is a testament to that philosophy. Varda doesn’t interject or impose upon herself a political ideology of her own, but listens through images, and by doing so, captures a lightning bolt of a moment in time and the people who lived to make it happen. By taking the cinema-verite approach her short becomes political in and of itself. She lets go of the control normally associated with a director and lets her camera glide over a people who have made their own political imagery and by trusting her instincts to look and absorb and become invisible she essentially hands her film over, making this one of the great learning tools of political cinema, as the politics are not directly associated with her own struggles as a French woman, but are understood regardless of her identity, because she listens instead of speaking.

An exegesis on motherhood with a distinctly second-wave feminist flair. Directors Chopra and Weill present motherhood as something worthwhile, beautiful in fits, even showing the full extent of a delivery, but also fully recognize the limitations it can place on a creative person who is trying to find her middle and satisfy both ends. In the 1970s that very question was under constant interrogation, with only the battle over reproductive rights taking precedent in the women’s liberation movement. Chopra doesn’t have answers and presents her question as a generational query that has plagued women for all time, and it is because it doesn’t have answers that it feels honest.

For a brief period in time the giallo was merely an excuse to let women show off the latest in fashion, and it is for that reason why I love the genre as it existed in the early 1970s. Yes, there was plenty of murder, but god, did you see what she was wearing?

Cheryl Dunye’s cinema in the 1990s combined a first person sensibility with these experimental tendencies that were rooted in youthful artistic pursuits like collage-making and diary. In Janine Dunye presents a potential relationship she had in high-school with an upper-class white femme girl and how sexuality did not supersede race. Dunye’s style is confessional in approach and resembles a filmic prose that could only be hers, because it is so rooted in the first person. When watching Dunye’s work it is easy to get the sense of understanding who she is as a person, and by extension, a shade of the queer world that is often neglected by the movies.

Shin’ya Tsukamoto’s art theater group Kaiju Shiata began transitioning some of their stage plays into movies in the late 1980s, and The Adventures of Denchu-Kozu was among the first. There’s a real spirit behind this gonzo short film that believes anyone can make a movie if they have enough guts to do it that I find inspiring on the surface. Tsukamoto and his art theater group were rule-breakers only because they had no idea what they were doing, and because they had no respect for how things were supposed to be done the images and texture they created did not exist before their anarchic metal philosophy of the human body in the midst of chaos. The result is a singular experience where vampires roast under painted backgrounds and stop-motion animation is used to replicate the dissolution of skin and soul under the weight of technological interference. Tsukamoto is most well-known for his Tetsuo: The Iron Man, which came out at the end of the decade, and in Denchu-Kozu he laid the template for a style that could only be described as his.

No one made war films like Samuel Fuller made war films. In 1951 Fuller made a pair of movies to chronicle the war in Korea that were partially funded by the U.S. Military (the other being Fixed Bayonets!). Fuller knew the horrors of war, being a World War II veteran himself, and having witnessed and shot some 16mm footage of the liberation of a German Concentration Camp. For Fuller, combat is something intimate and wholly ambivalent, which separates him from the rah-rah war pictures of his time and the looming political films that would ultimately spring out of the Vietnam war. There’s nothing monumental, epic or grand about what Fuller does and his approach humanizes his men, not as heroes, but as regular men doing a job, and that job is horrible. These hardened men don’t take the time to recognize that it’s bad, because if they did, it might get them to thinking too much, and too much thought will doom a man who has to be precise in order to keep himself alive. In The Steel Helmet Sergent Zack (Gene Evans) wears a testament to his burrowed time atop his head. He only does what he can. War is hell, but what else is a man supposed to do? Fuller makes War a story of people instead of people a story of War.

Scuzzy avant-garde exploitation that seems completely restless on a level of form and texture, and thus pushes early digital cinema to a breaking point. Within that constant reinvention there are doses of Japan’s V-Cinema of the 1990s, girl gang movies of the 1970s and Verhoeven’s Robocop with messianic digressions that feel like kindred spirits with Lynch’s “Lady in the Radiator”. This is a movie that can barely keep itself alive as its constant state of transformation seems to suggest that the well-spring of potential images and ideas must eventually dry up, and it is thrilling to watch this movie attempt to sustain itself as it gushes blood and static out of its own self-inflicted wounds.

When I was working with Vulture on their list of the 100 Most Influential Animation sequences I got the chance to watch a lot of animated short films that I hadn’t seen before and none moved me quite like Karel Zeman’s Inspirace. Animation on glass is quite frankly, an astonishing proposition in and of itself, but to watch it in action is to bear witness to the elasticity and beauty that is possible in a cinematic art form that seems to have no limits. Zeman is one of the great innovators, but he was not merely an inventor. His movies are abundant with depth, texture and contain a dreaminess that is easy to admire. Inspirace suggests that glass could move like water and in Zeman’s hands one can’t help but believe.

Streetwise could have easily been an exploitative nightmare in the wrong hands. A portrait of children who have slipped through the cracks and are hustling on the streets, only barely surviving, has such a narrow margin where it could be considered a worthwhile pursuit, but Martin Bell and Cheryl McCall rarely step over the line. Their images have a cinematic, timeless quality, that is not common within the documentary subgenre where camera placement and movement could be done with ones eyes closed. They aim much higher, and give these kids an immortality of restless youth that will always be relatable to teenagers who feel the need to run away or in some cases divebomb into the sea. While there’s a beautiful sentiment in such a gesture, Streetwise is also a graveyard, made abundantly clear in the end, that this life isn’t romantic and that juxtaposition is only a shield for the very real hurt that these kids have been forced to endure for what can only feel like their entire –short– lives.

A favourite of David Bordwell’s and a favourite of mine, because there’s a digression where the confident, refined melodrama is put aside when Doctor Toshiro Mifune decides to stop practicing medicine and begin performing Mixed Martial Arts on some hooligans. Every film should do this.

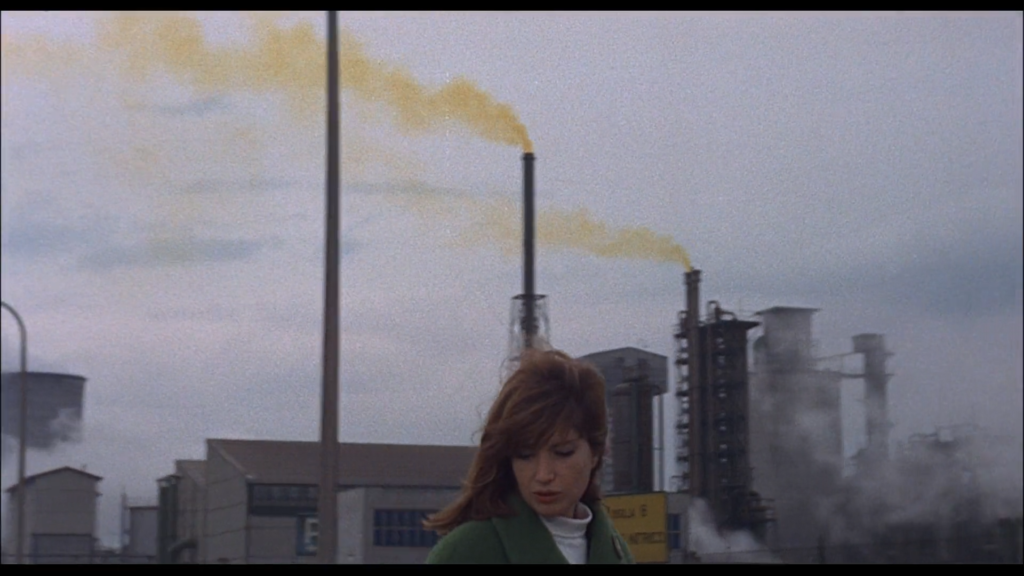

There’s a lot of quiet distance in Antonioni’s images and that could potentially prove to dissatisfy when making a movie which hinges on the acting of the star, but Monica Vitti understands that there is a complexity and a reason for why this character would want to make herself small. Antonioni’s larger messaging on pollution is blunt and understood, but only as an extension of Vitti who spends the entire movie in a slow dissolve of the self.

Rock and roll cinema. The world’s gonna end baby, might as well drive that car right off the cliff. If the body needed whiskey to thrive instead of water. Japanese Noir has a way of doing away with the grander thematic threadings of the American equivalent and instead embraces a nihlism that frees the genre up to only prioritize the shadows, the sex, the guns, and the freedom in knowing we’re all gonna die anyway.

In an interview on the “Movies that Made Me podcast” Allison Anders told a story where she sought out the help of Martin Scorsese when making “Things Behind the Sun”. She needed to watch the great movies about rape before she made her own and after watching the few that weren’t steeped in genre she felt that Ida Lupino’s “Outrage” was the only one that affected her on a personal level. When watching “Things Behind the Sun” I thought about my own history of watching movies about rape and how there was rarely ever a cathartic feeling for me after re-litigating my own trauma through art. “Things Behind the Sun” handles the subject with honesty and Kim Dickens performance is frustratingly astute. Her inability to remove her damage and evoke that through an angry petulance made me feel like my own time spent screaming into pillows or wandering around my house telling myself “don’t think about that” wasn’t in vain. But the double-edged sword of all this art-trauma-art cycle is when Dickens’s character writes a song about her rape that suddenly gets popular, that outlet of art becomes a problem of its own. Was it cathartic to get it out and was it worth it to create this echo of your worst moment? That’s an unanswerable question.

The Watermelon Woman is a radical film, because it takes the history of cinema and its neglect of black actors and actresses and creates an entire avenue of visibility all of its own. When you don’t have a foundation in cinema history you have to create your own culture. It doesn’t matter that The Watermelon Woman didn’t actually exist, because ultimately she did. Hollywood wasn’t there to capture her so Cheryl Dunye did. She pulled a wisp of smoke out of the air of the past and gave her flesh for a new era.

Be First to Comment