Body Talk is an ongoing series of transcribed conversations on Transgender Cinema as the two of us prepare to write a book on the subject. This installment of Body Talk is on the trap narrative in genre cinema.

Willow Maclay: If I were ever in a situation where I had to start dating again I would fear for my life, because I’m perceived as a cisgender woman by society at large, but I am not one. I’m an actual living late plot twist, and if someone wanted to murder me for this reason they likely wouldn’t face jail time. I would have it coming, because I was a liar. I was scary. I pushed him too far by saying I was something that, let’s be real, no one considers you are, unless you’ve had surgery, and I haven’t had surgery. That’s still some time away, and it could always be pushed back again, so I live as a late act twist that never had to be revealed, because I’ve been fortunate enough to fall in love with a man who loved me for me, and wasn’t threatened by the inbetween-ness of my genitals.

This is not the case for most people. I am not the majority, and I am lucky.

In a larger cultural sense it all started with Psycho (1960). It was the late act reveal that a character wasn’t who they were supposed to be, and it was the demonic femininity of men in dresses and lace that became the lasting image. Yes, she was stabbed in the shower and the music pierced us all, but the killer behind the blade was a man who thought he was a woman, and genre filmmaking have been milking this for all its worth ever since.

This doesn’t happen in real life, but the closest image we have to the manic tranny with a blade between her legs is that of actual transgender women. We are the broken and the damned and worse than that, we might just be psychotic. We might just kill you. There are more instances of trans woman appearing as murderers in movies than there are good films featuring actual trans women in meaty, acceptable, dense roles that approach their humanity with something resembling respect for the difficulty it takes to be trans. The murderer has persisted. We haven’t.

In this segment of Body Talk we’re going to be discussing that plot device. Caden, when did you first see a movie that used this narrative trope?

Caden Gardner: We’ve talked about this in the previous installment of Body Talk that primarily dealt with cis actors in trans roles. That conversation also spilled over into cheap third act reveals of characters who, ‘Are not what they appear to be’. Some of that ranged from The Crying Game to Ace Ventura: Pet Detective. These characters are not murderers, but unstable and in the latter’s case a villain, with the comedic effect of the reveal played for gross-out laughs and showing how normalized the trope had become. I remember the ongoing gag in the Austin Powers series of removing a wig from a character who appeared to be a woman with Austin exclaiming, ‘It’s a man, baby!’ So I saw the jokes first, how situationally, the panic and anxiety was normalized by the status quo and how the ugly stereotypes within those fears became the punchline. Then I got into the fear and panic at the heart of earlier films than those comedies.

Now I had seen Psycho but I always found Norman Bates an incredibly sympathetic, tic-filled, ball of anxiety. Anthony Perkins gave Norman depth, layers, and even humanity, where you can retroactively, after the twist, realize how at war he is with himself. Hitchcock allowed you to root for him when he was covering up Marion Crane’s murder by sinking the car. I had seen Gus van Sant’s Psycho remake which sexualized Norman’s voyeurism. Van Sant opted for a shot for shot remake so the contemporary knowledge of this twist informs everything Norman does, and after so many Psycho knock-offs where transness is at the forefront and tied explicitly to the twist it becomes an entirely different experience, and not a better one. To move away from Psycho, slightly, one such example of this trope that I came to know very early in my life was Robert Hiltzik’s 1983 slasher Sleepaway Camp.

I’d like you to get into that, but before I do, Willow, as I think you eloquently stated your position on that film and twist in Cleo a few years back.

WM: I similarly don’t have many problems with Psycho, even if I think the last ten minutes is an unnecessary and ultimately clumsy act of explanation. What separates Psycho from many of the films we are going to be discussing in this installment of Body Talk is that it is not fundamentally hinged upon the twist ending. There’s a lot going on in Psycho and cinephiles, at least, remember much much more than Norman’s cross-dressing and murdering. The craft in that movie is maybe the zenith of Alfred Hitchcock’s career. If one wants to argue that Hitchcock was a master of control then Psycho is the last movie where that is easily apparent. I find his period after Psycho fascinating, because he loses grip of his movies, but that’s another conversation. Psycho is a totem for a reason and I love it, even if it unintentionally spawned many poorer copy-cat films.

One of these is Sleepaway Camp , which you brought up. I’ve seen that movie a half-dozen times for one reason or another. The only movie I outright hate that holds that distinction. I wrote about it for Cleo Journal, but the gist of my problem with Sleepaway Camp is that it intentionally makes the reveal horrific and the movie only works as a late act plot twist. Everything beforehand is slop to say the least. If it weren’t for the fact that these filmmakers wanted to show a girl with a dick the movie wouldn’t be remembered. One could argue that final scene is useful in pointing out how cisgender people view transgender bodies. I don’t think that’s a bad idea, but I think it’s a cynical one, that doesn’t carry as much weight when placed against the brunt of that characters struggles to deal with her own body. Angela isn’t trans, but her body is how cis people perceive transgender bodies and the co-signing this film has for the horror of the onlookers is damning. It’s a horrifying image to have Angela slack jawed, completely nude, caught in mid-scream, heaving like a demon. It is even worse that those onlookers react with total disgust of her body. They don’t find her murders horrific, but she has a dick? That’s the scariest shit ever. There’s no covering that up and reclaiming the image. It’s the only image people talk about with Sleepaway Camp, because the movie is otherwise shit. It’s canonized, because of that image. An image that doesn’t have the cultural staying power of Buffalo Bill tucking in his genitals, but it is nevertheless synonymous with the phrase “chick with a dick”. Being one myself, I can tell you, it’s not all that tantalizing. It’s boring, mentally arduous on a personal level, and tucked away all of the time, but that doesn’t sell. Flaccid never does.

CG: Sleepaway Camp makes Angela (Felissa Rose) a timid creature (and I do mean creature, the film is too trashy and low-brow for any humanity in anybody, but especially her) that then becomes a dehumanized monster by the end. It dates back to her crazy aunt that the audience gets doses of through flashback. Angela is forced-femmed (for lack of a better word) by that aunt, her history rooted in a trauma to a horrific accident that claims members of her family, that includes her sister, the real Angela, that is shown in the flashback that begins the film. So Angela is living as a woman and being socialized as a young feminine girl. This was not her choice or inherently innate to her. She never outright states that she saw herself as a woman. I recall that people treat Sleepaway Camp’s twist as a surprise but the film does leave clues that honestly have the subtleties of anvils. Angela is confronted by girl bullies for her timidity, sniffing her out like she has something to hide from the get-go. She doesn’t go swimming, she doesn’t take her clothes off, and she does not shower in the presence of others. As if saying to the audience “What’s up with that?” and these bullies will not quit trying to figure her out. What is disturbing about this film for me is that it emboldens the suspicions of those wretched characters by having that twist with Angela exist. The film, unintentionally, almost predicts gender gatekeepers who want to harass any ‘not normal-looking’ person who goes to their preferred bathroom or dressing room of fucking Target in Anytown, USA that can then extend into law with not so enforceable anti-trans bathroom bills and ordinances in those areas of the country. I think there could have been many films where the version would be to humanize Angela, or give her depth, a sense of who she is or how she relates to her body in being socialized female when she has this whole history about her. But she lives by the twist and dies by the twist in that image that is haunting not for the body count she leaves, but in how the film can treat that character type, thinly drawn mind you, with such animosity and inhumanity.

People can be quick to dismiss any concerns about this film as, ‘It’s only a movie’ or ‘It’s just a cheap slasher’, but for me we have gone through a lot of genre films that explore the body and gender in fascinating ways and also see how even when seeing real monsters like Jame Gumb in The Silence of The Lambs, that there can be moments of humanity in seeing pain and confusion and not just a cheap twist, thrills, and kills.

WM: As a diehard fan of the genre I’m typically more forgiving of horror films for being uncaring, but I think Sleepaway Camp is merciless in a way that isn’t fun to watch at all. I’ve heard better things about the sequels, in that, they have a sense of humour about the subject matter, but I haven’t watched any of them to date. I know Laura Jane Grace (Against Me!) is a big fan of Sleepaway Camp, but I don’t see the value in reclaiming it unless you take up an entire fuck the world attitude, which I wouldn’t begrudge any trans person for having, but that isn’t me. Moreso than being offended, I find the entire affair just catastrophically boring, even for the relatively conservative structure behind slasher films. My main issue with Sleepaway Camp, beyond the obvious, is that if they were going to go with that ending why not lean all the way into it and make it so completely offensive all the way through, negating the twist, and basking in the glow of being a fucked up movie instead of half-assing it by sweeping the big reveal under the rug? It’s just annoying, and it’s not the only movie of this type to exist. In a larger cultural sense though, it’s probably the most famous example in the horror genre of this trope outside of Psycho. Sleepaway Camp definitely has more cultural staying power than something like Brian De Palma’s Dressed to Kill, which annoys me all the more, because at least Dressed to Kill has the common decency to be well made. De Palma, as much as he annoys me sometimes, was never asleep behind the wheel. He always directed something 100%, but Sleepaway Camp? It’s barely a movie, but in the horror community it has been canonized. Their opinion being that It’s worth getting through the slog, because you’ll get to the girl with the dick. The only image in the movie.

CG: The early 1980s Slashers, basically Friday The 13th (speaking of a Psycho rehash) and after, had a habit of being in conversation with the genre by responding to one movie’s ridiculousness- be it kills or twists- and outdoing it. Resulting horror films were in conversation with Friday the 13th , because it was a huge success, and even Friday the 13th itself was in conversation with Psycho and Halloween (1978). They took the twists and the formula and embellished it in their own mold, but the results, were as you state, half-baked and cheap. I probably do read like a moralist, I actually do love a lot of the horror films from that era, even some that are well, not exactly expertly made cinema and have a nihilist streak about humanity, but I find the canonization of that film to be a mistake in taste. I am sure some of the appeal is the sleaziness and trash, the lowbrow of it all that horror nerds can embrace in ways cineastes and more mainstream audiences do not.

This brings up Brian De Palma. His cinema is sleazy and trashy, but well-done in a way where his commanding scope and playfulness in artifice gave him a lot of respectability (his fans ranged from Pauline Kael to Quentin Tarantino) and currency that still endures today with a lot of cinephiles and film critics in our age-group. He recently had a birthday which on social media seems to give an opportunity for cinephiles that I follow to rank his films. Unsurprisingly, even if I am left quite disappointed, Dressed To Kill seemed to come up frequently as a favorite of people who profess their love of De Palma. I always have an impulse whenever I see it come up in conversation to explore why people like it and reconcile that with the fact that it is definitively a transphobic film.

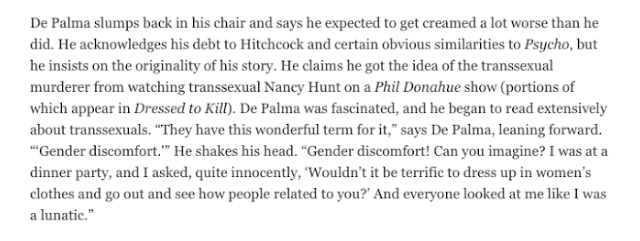

To be clear, I do not want to #CancelBrianDePalma or act like there’s a moral failing on the part of these people, some of whom I do consider good friends, for liking the movie or finding something to like in the film. I have curiously heard people who have written books that feature Dressed To Kill, state that it is not about transness but goodness. But I bring you this: from the maestro himself who was informed entirely about the film’s transwoman killer from real-life trans woman Nancy Hunt whose story from Phil Donahue he places into the narrative of his film. It is an unsubtle wink and clue of the twist that still angers me upon reflection.

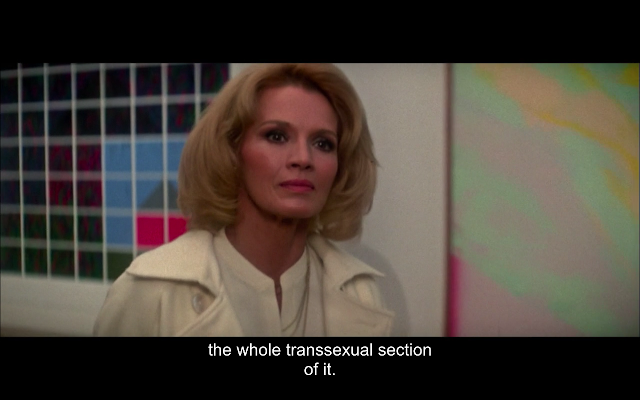

WM: I’ll start by being very upfront that Brian De Palma and I have a complicated relationship as filmmaker and viewer. I adore some of his films and consider them to be all time favourites, like Carrie, which we’ve both praised, and Blow-Out, which is without a doubt one of the best films of the 1980s. My issues with De Palma, and these issues are only mine, is that I’m annoyed by his treatment of women. I get frustrated that, without fail, especially in this period, they seem to be killed in exceedingly gruesome ways after their sexual usefulness has been wrung dry. De Palma’s a very horny director, which is fine, but I don’t get a huge thrill out of watching him have an obvious hard-on for the women in his movies. Does this make me a prude? Probably. Does it make me a hypocrite, because I love Dario Argento, who does basically the same things? Also probably. We’re made of contradictions. I’m allowed to have mine, but with Dressed to Kill it is a different issue entirely, and that’s one where I think he runs into this gigantic problem of mixing the absurdity of the late act plot twist in Psycho with real life problems transgender people have. Psycho is not a relatable target in any estimation, but Dressed to Kill certainly is for two reasons. First the inclusion of Nancy Hunt and also due to the discussion of sex reassignment surgery which is a mirroring scene explaining transness, poorly I might add, that is an homage to Psycho’s transvestite explanation. Norman was never a transvestite in Psycho, but Robert Elliott is canonically transgender and De Palma uses that as a crutch for his worst tendencies as a director towards things like castration anxiety, the femme fatale and domination.

The problem is that all of these autuerist tics are only noticeable in the form if you’ve seen half a dozen Brian De Palma movies, but if you’re coming to Dressed to Kill as a new viewer it just looks like a blanket “psycho tranny killed women because she couldn’t be one herself” story. I’m not saying movies have to reflect reality and every movie about a trans character has to be nice. Far from it; what I am saying is that it becomes a problem when something that works on an individual level becomes a pattern, and the murderous tranny is definitely a pattern. I have much less problems with these movies compared to the issues I have with the trope. I think Dressed to Kill, in particular, is a really well made film, but when you’ve seen this story more than a dozen times it becomes boring, and it doesn’t really do transgender people any favours in real life that our entire cinematic language hinges on a late act twist.

Did I ever tell you the story of when I came out for the first time on a film forum back in 2011? Well, one person commented, and I’m still friends with this person, “what a twist!”. If that isn’t transness at the intersection of movies I don’t know what is, and the shame of it all is that we could be a lot more if given additional narrative space.

CG: You never told me about that! I felt similarly that when I came out online- and I admit to being pretty guarded about my online anonymity for a very long time- that there were days of reverberations where some responses were akin to it being a twist ending. Not all gave this commentary of ‘I didn’t have a clue’ or ‘I didn’t see that coming’, but many did see it as a narrative of sorts, as though I had planted and stunted this as a plot thread when in actuality, I was in a very bad place mentally. I felt helpless and it felt was necessary that I come out because it was an election year and one side was absolutely more hostile and transphobic than the other (hint: it wasn’t the Democrats). I have mixed feelings about how I went about it- but that was mostly because I was also in an alcoholic fog and my nerves and mode of behaviors operated differently then as opposed to now, which hey, now I actually am open, out, and have a lot more control because I am transitioning and not trapped in hostility, shame, and the closet.

Now back to Dressed To Kill, I looked back on the way the film was seen then and now, constantly feeling disappointed that nobody who seems to want to champion the film can really ever confront ‘the twist’. It can often just be mentioned in a sentence, admitting to trans woman serial killer as ‘cartoonishly stigmatizing’ as The New Republic did a few years back but at the same time declare that critics should surrender their prudish sides and embrace DePalma’s ‘pure cinema’. Or you can talk around it, in the name of spoilers I suppose, and just use catch-all phrases as ‘sleazy’ or ‘bizarre’ in the twists the film has. Some do not so much dismiss the transphobia but label it as pulp treatment of something real. Then you have a little more problematic readings, some of which I think unconsciously white-wash the transphobia of the maker, by labeling Robert Elliott/Bobbi as schizophrenic and pretending that was DePalma’s intention when he admits he crafted and was inspired by trans women and then linking it to Jekyll & Hyde ‘two sides’ of a person who switches upon sexual stimulation. Now, of course DePalma’s knowledge of transness is off as he only sees the surface but he made a deliberate choice to insert Nancy Hunt’s own image in his movie. He uses clips but if you look up Nancy Hunt, you would also know that she similarly rejects trans as trauma and trans as pathology, viewing the mental health community as hostile towards trans people rather than helpful to her and many people in her position. Hunt lives forever in certain transgender archives but she is used ghoulishly in a film where the director laughs and chuckles like the Keith Gordon character about the idea of a trans woman.

Keith Phipps, to his credit, did confront the transphobia of the film when Dressed To Kill was released on the popular arthouse label The Criterion Collection. But he appears to be an anomaly to cinephiles and critics that probably do not really see the problem of the movie in the way that you and I do. As far as De Palma himself, it perhaps comes off like I hate him. I hate this film, although I find it revealing in ways that he may have not intended, even beyond the transphobia. But I like a lot of his work and quite a bit of it is built within his sense of cinematic language and artifice. However, as Kam Austin Collins succinctly put it in his Letterboxd log, you may love that Museum of Modern Art set-piece, the split diopters, and unreal quality of the moviemaking of fake outs upon fake outs but, “The transphobia is real”.

WM: I love Kam (read him at Vanity Fair). For my money he’s the best working film critic right now, and he’s absolutely right. Dressed to Kill does have an unreal quality of moviemaking that lays on top of this pretty vile center. Isn’t it frustrating that Brian De Palma may have more natural talent as a director than maybe anyone who has ever stepped behind the camera and he mostly uses it to worry about his dick? As far as just pure fucking cinema there are few directors with more skill or have made movies that are as luxurious to watch as De Palma. However, more often than not he almost always does something that creates distance in my ability to fully appreciate his works, and that’s most readily apparent in Dressed to Kill, which is a movie I championed before I came out, but afterwards was hesitant towards showering praise upon. I could more easily ignore the shitty political nature of the movie before I came out, because I was foolish enough to think that wasn’t me, but now I just find it annoying. I’m not even offended by its clumsy handling of gender politics, I just find it dull. Like, by the end it’s, “oh this is obviously a riff on Psycho. I don’t give a shit”. De Palma was like his dad, Alfred Hitchcock, in his ability to completely control all aspects of technical filmmaking, but De Palma’s career is without the same barriers Hitchcock had which negated some of Alfred’s worst tendencies toward women. As a stanch supporter of Marnie, I’d be wary of calling this a bad thing, but it certainly makes me wonder what Brian De Palma could have done in a system where some of his decisions were checked a little more often, because Dressed to Kill is almost embarrassingly a copycat of things better than that movie: Psycho, and giallo plotting. Even the films best scene: the elevator murder is lifted almost directly from the climax of Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion, even down to the outfit Bobbi is wearing.

CG: “Isn’t it frustrating that Brian De Palma may have more natural talent as a director than maybe anyone who has ever stepped behind the camera and he mostly uses it to worry about his dick?” That is a pretty inescapable route to take for even his admirers, as the Jake Paltrow-Noah Baumbach documentary on De Palma shows (and I would recommend watching in relation to some of his films and again, De Palma’s unconscious revelations and confessions about his own relationships to his work, other films, and his personal life). When Pauline Kael, notoriously anti-Hitchcock but pro-De Palma, gave a write-up on Dressed To Kill, she wrote that De Palma has a self-awareness that makes his films have a vein of humor due to how open De Palma is open about his id, “What makes it funny is that it’s permeated with the distilled essence of impure thoughts. De Palma has perfected a near-surreal poetic voyeurism—the stylized expression of a blissfully dirty mind,” believing that Dressed To Kill is a great example about the inherent voyeuristic nature of movies. And I get that appeal and how uninhibited De Palma is, but it is also why I find Dressed To Kill narrow. He was in therapy at the time, but seems to hate psychological readings of the sexual stimulation of a beautiful woman when aimed at himself or his characters.. And of course this male gaze has a certain preferred image of a woman. It is a cisgender woman, not women like Nancy Hunt as he clearly does not consider trans women to be women at all. The uninhibited nature of his work that exists in Body Double, such as the ‘Relax’ sequence, does feel more genuine and not as isolating as opposed to Dressed To Kill where the authorial voice of the film finds people like myself to be disgusting and something to laugh at, or consequentially, nightmare fuel. Dressed to Kill notoriously opens with an insert of a naked woman in the shower that is supposed to be Angie Dickinson’s character- but is so obviously not and De Palma knows it- and if that’s what turns the guy on, then good for him, but he clearly sees trans women as men clothed head to toe in wigs passing through and absolutely not wanting to explore anything beyond the surface. It always frustrates me that when a bad boy director is celebrated for liberation and rebellion , but ends up showing there are actually lines drawn in what they find acceptable and that the ideas of other kinds of people existing beyond their ideal, coveted image of femininity go ‘too far’ for them.

While De Palma’s biggest fans that I know are straight men, I do know plenty of queer people and cis women who also think he’s great, but this film was enough to keep me at a distance. What’s not to like about De Palma?’ was something I’ve heard. Hell, when I read a recent piece on Dressed To Kill it said verbatim, ‘If you don’t like this [Dressed To Kill], then you don’t like movies.’ I know that people often are in the mood to rehabilitate Dressed To Kill as, like William Friedkin’s serial killer film Cruising, it had protests and vocal dissenters for the movie at the time (not for the transphobia to be clear, but for the violence against women in the film— at the hands of the transgender serial killer). It was a film that in De Palma’s own words did good business. Yes, it got Razzie nominations (I mean, so did Kubrick’s The Shining) but I think the canonization and reclamation of Dressed To Kill for the canon missed more points of view along the way in terms of looking at it now and its cultural significance. But it is a lot more attractive to treat the film as an object of buried treasure or hidden gem which Dressed To Kill is treated as than it is to listen to a dissenting opinion.

WM: I know plenty of trans women who love Dressed to Kill, as well as Sleepaway Camp, and I find no problem with this even if I have my own issues with these movies, but I would genuinely love to hear what it is about those two in particular that speaks to them. Maybe it’s a level of honesty from cisgender voices of how we’re actually viewed without the semblance of political correctness bearing tolerance of our own gender? Or it could be as simple as thinking Dressed to Kill has stellar camerawork and Sleepaway Camp is too goofy to take seriously, and again, these are good enough reasons to like a film, but I have larger culturally specific reasons why these movies in particular rub me the wrong way. One major issue I have with Brian De Palma protesting to psychological readings of his movies is that if we were to push away at these things then I’m unsure what depth De Palma has other than as a sexual charlatan or his admittedly, fantastic camera work, which again, is fine, but I find that lacking in girth. De Palma is most interesting to me when I’m trying to figure out how he feels about women in his movies, because that’s absolutely his central hang-up. The Fuck and Kill mentality. Marriage never really comes into the equation. I can see on some level why cisgender women like De Palma’s women and his eroticism, because it’s brutish, tough, and these women are generally arsenic and don’t give a fuck and there’s definitely something appealing in that, but his treatment of transgender women is completely fucking different. We’re the great American nightmare. The total destruction of the male body. The malleability of our flesh into that of a woman’s is horrifying to him or at least perversely interesting, which might be more honest than not, but when I watch Dressed to Kill I get the sense that he finds bodies like mine absolutely disgusting (disclaimer: I’m closer to Michelle Pfieffer than Michael Caine, sorry Brian).

Part of me wonders if Brian De Palma could potentially have bedded a trans woman by mistake and then felt his heterosexuality capsize as a result. I don’t think that’s an insane thing to think, no? Pure speculation on my part, but he has this strange mixture of self-hatred and lust when talking about or engaging with transness. In the cinema of De Palma if the body of a woman is the ultimate act of cinematic ecstasy then the body of a trans woman is the total destruction of orgasm. A trans woman is castration, and therein lies his greatest anxieties. Dressed to Kill is fascinating for these reasons. It’s the kind of movie you could talk about all day in the context of De Palma’s work. Where it’s more boring is in the greater landscape of trap narratives in movies where it’s mostly the same old thing.

CG: Yes, we are not seeking to bury and ban Dressed To Kill, but the film’s significance is tied to a trope that, as we noted, involves revelation or a twist that’s tied to transness in this negative way. And I totally get your speculation on the root of where this came from (De Palma insists it was just from seeing Nancy Hunt he also grew up in a New York City where the Warhol Superstars were in the same film underground he started in the late 1960s, I find it unbelievable if he did not find himself in the same space- if by pure incident- with cross-dressers or trans women at some factory party to watch independent films), as I often speculate why does there exist moments in movies where a pickup of a trans woman for sex leads to a shocking revelation and male outburst for being ‘tricked’ (think Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting). Even on a more intellectual level, I wonder what is Jesse Singal’s deal (and I am not alone) over his obsession with trans women in his writing. But to get back to our mining through this narrative, I want to return to Psycho as the genesis even if it is not dealing with cross-dressing or gender dysphoria. We have of course talked about the riffs and knock-offs but what is fascinating is how quickly the knock-offs also produced the connection of this reveal to the villain or killer ‘not being who we think they are’ as far their gender and done so in genre-film, B-movie fashion.

WM: There are so many throwaway scenes of cis men fucking trans women and throwing a fit that give absolutely nothing back to the movie it would be impossible to count them all. This goes doubly for throwaway scenes where cis guys clock a trans woman and make fun of her. This even happens in Zodiac (2007) of all things, and I can’t for the life of me figure out why that scene in particular exists. Is it to reaffirm we’re in San Fransisco and cops are jerks? Seems pretty fucking basic considering Fincher, but that scene has also stuck out to me as a microcosm of issues of transness depicted on screen, and in a larger macro level when that scene is pulled out to its fullest length that’s when you get things like Dressed to Kill. I don’t think cis people get how fucking exhausting that is and how much you have to reconcile to watch movies and realize that these things are just going to happen. Or even, god’s inferior child, Television. For example, There is not a sitcom that exists that won’t take a jab at trans people, and we don’t even worry about these things, because there’s bigger fish to fry with our own issues. Like our passports being denied and the living hell that is the current government of the United States.

CG: William Castle’s 1961 Psycho knock-off Homicidal is a doozy and laughably trashy in its twists and turns. Its killer is a double-role for Jean Arliss (a pseudonym for Hal Ashby’s wife Joan Marshall) who plays Warren and Emily. So the twist is that the audience sees Emily commit murders and she notably, despite being described as Warren’s fiancee, is never in the same room as her groom-to-be. In the dialed-up, pure William Castle, 3rd act Emily is revealed as Warren, complete with a classic wig removal. Then, much like that awful psychologist explaining it all in Psycho, we get an explanation. Warren was socialized male but- and this is where it really gets crazy- he was biologically born female. His father wanted a son and his mother insisted to keep up the stunt (that apparently worked in ways that are a little unclear— I don’t think Castle and company thought all of this through but complaining about plot-holes from William Castle is just barking up the wrong tree) that included the county clerk marking the birth certificate male. I think there was far more work done to Warren in this ‘forced masc’ tale as we get an allusion to Christine Jorgensen’s sex-change operation by the line, “Then Helga took Warren to Denmark. What happened there, we don’t know”, as the American Jorgensen in the 1950s got her operation in Denmark (similarly, Ed Wood’s 1953 film Glen or Glenda was inspired and marketed as being connected to Jorgensen’s story that caught global public attention). Warren became Emily, fully living, socializing, and possibly getting the medical assistance in hormones and operations but returns home to collect inheritance money, having to return to Warren, a life full of trauma, confusion, and haunted by ghosts and figures of her past. The film is silly and as I speak to the characterization of Warren/Emily deeply problematic, but I see this as necessary to point to the fact that the evolution of the Psycho narrative is more than just Ed Gein (who also inspired The Silence of The Lambs). Clearly, this narrative has been a point of entry into some of the biggest tropes and misconceptions about transgender characters.

WM: I find William Castle’s capitalist urges really earnest. He was a the filmmaker equivalent of a big tent ring leader of the wackiest carnival that ever came to home and there’s something appealing about that kind of salesman. It’s hard to be offended by someone who made The Tingler and whose sole interest in life seemed to be scaring teenagers right at the point where they started to make out during his terrible movies. Homicidal isn’t really any different than the other movies he made, but of interest to us, because of some gender fucker-y. Earlier in this installment of Body Talk I said I wouldn’t have as much of a problem with Sleepaway Camp if it knew how to lean into the absurdity of its source material. Well, this is exactly what I’m referring to when I say lean into your batshit insane idea. So, it’s more fun than harmful. It’s difficult to raise your pitchforks over something this silly, but let’s get into something that is silly on paper, but isn’t in execution.

Caden I want to know what you think of Sion Sono’s Strange Circus, because it flips the gender on the opposite spectrum of this typical trope, which more directly effects you.

CG: I’m admittedly not well-versed on Sion Sono’s cinema and Strange Circus was, to my knowledge, the first film of his that I’ve watched. It is fascinating as it does go back to you mentioning the exhaustion of viewing media as a trans person, where these movies constantly clock or misgender their characters. The character, Yuji (Issei Ishida) is gender fluid but believed to be male assigned at birth assistant to our protagonist. Yuji is constantly peppered with uncomfortable questions about his ‘asexual’ appearance. For a film that is full of sex, rape, and trauma, Yuji at first appears like a sissy stereotype for his long hair (in being trans male, it is admittedly difficult to ‘pass’ with long hair, although Yuji’s hair veers close to David Bowie in Labyrinth) and lanky physical appearance. Basically, Sono’s rude, invasive characters who quiz Yuji about his look are proven right with Yuji admitting that he was actually a female assigned at birth and that his traumas and mental illness inform his identity which to that point, then becomes synonymous with his trans identity. How predictable, how boring.

What is disappointing is Sono desperately wants to be among the misfits and outsiders, with Strange Circus having a kind of cabaret pretension, as this is where the film starts and ends, the film’s named after this club of cross-dressers and drag queens. The extremity that Sono likes to fashion that he is doing though, much like De Palma’s limited uninhibitedness in Dressed To Kill, falls short with the ‘tranny as killer’ trope. Yuji is unstable and in a circle of rebels with piercings and body modifications that symbolize their identity that are remarkable changes in their physical appearance, when Yuji reveals to them his ‘secret’ these exhibitionists are now shown mouth agape. Hypocrites. Yuji is seen as going ‘too far’. I’m reminded of Dressed To Kill of the lead character being haunted by Yuji in her dreams much like Robert Elliott/Bobbi haunts Nancy Allen. It is the flip side, so this is to say, trans men, although not as frequently, also take it on the chin in the trap narrative, which for every banal shot taken at androgyny and transness in something like a square family sitcom the trap narrative also finds its way into certified “cool” film directors like De Palma or Sono.

WM: So many of Sono’s films seem desperate to me, and while I like some of them, like Love Exposure and Suicide Club, I find his tics really aggressively on the nose. He’s working in a similar mode as Takashi Miike where he tries to follow these outsiders and misfits, but fails to capitalize on his freaks. Miike on the other hand sympathizes, pointing to a cultural reason for “why” these characters are outcasts, and emphasizes their own humanity, even if they turn out to be evil characters. Miike makes sure his characters are heard, even if they’re wrong. Sono on the other hand just points and asks the audience to “look”. Strange Circus is the worst film of his I’ve seen, because it so desperately wants to be trangressive and taboo in a really intellectual way, but what does it have to say about gender at all really? I can’t think of anything, even in the context of Japan’s more easygoing nature towards drag queens and cross-dressing in their entertainment. In Japan these representations are typically played for laughs, but like a trojan horse they emphasize the faults and struggles these characters face, which honestly gives them more depth. That’s key in genre cinema anywhere on any subject you want to tackle, but with Sono I typically don’t see depth and that is never worse than in Strange Circus. I don’t get why anyone would want to check out this movie when Visitor Q exists. That film is complicated, uncomfortable, formally daring but has guts in what it’s actually trying to convey about gender, family units and violence. The only new wrinkle in Strange Circus is that the gender of the typical trap trope is reversed, which is maybe meta, but it’s certainly thin.

CG: I thought a lot about the cultural context in Japan with Strange Circus and just found that I got a lot more out of twisted Oedipus Rex snapshot of ‘gay boy’ culture in Japan from Toshio Matsumoto’s 1969 masterpiece Funeral Parade of Roses as far as transness, and outsider narratives go. I similarly feel like I’ve only scratched the surface with Miike but I definitely agree with you that I sense he gives his characters a better chance for the audience to understand and even empathize with their extremities and peculiarities. It really can make a difference as far as saying ‘pay attention’ to the audience rather than insist on the audience give a gawking ‘look’ when it comes to portraying trans people in film.

And to go back to misfits vein that Sono strives for but falls into the trap narrative trope, I think about Tetsuro Takeuchi’s Wild Zero where a character is revealed to be trans and while the male protagonist becomes incredibly anxious and put off initially about this revelation Takeuchi has the film’s Greek Chorus, the J-rock band Guitar Wolf, tell the lead character Ace that love has “no boundaries, nationalities, or genders” and that he should get over that hang-up and follow his heart, which has him be in love with the trans woman, Tobio. Wild Zero does not really subvert the trap narrative (the body reveal happens), it confronts the anxieties around initial stigma in being trans and in love and falling in love with a somebody trans and then just goes with it in a pretty sweet if simplistic way amid the backdrop of an apocalyptic zombie invasion (there are just bigger fish to fry!). I dig Wild Zero for many reasons but it being a respite to the trap narrative goes a long way for me.

WM: I think with films like Wild Zero, various work from Takashi Miike, and even aspects of Homicidal we can see an “other side of the coin” effect with how to handle transness and typical tropes in genre cinema. Whereas some of the other films we’ve discussed like Sleepaway Camp and Dressed to Kill fail in various ways. I don’t think the intention we ever had here is to say that genre cinema is bad from a moral perspective, but that it needs to be smarter about applied tropes. I think there is a good film to be made about the trap narrative in genre cinema by subverting it and shifting the positional power therein but I haven’t seen one that quite fits what I’d want yet. I don’t need an empowerment movie necessarily, but one that understands the game, and by and large these directors who work primarily in genre cinema that we’ve discussed thus far, struggle with these things, and it comes back to needing more trans people involved in cinema. When our perspective gets heard. maybe then the narrative will shift from the trans woman who is a trap and in turn a murderer to the trans woman whose trans status is revealed and more likely to be killed, because that’s the reality underneath the trans trope. We’re the ones that suffer both in cinematic representation and in reality where we face the danger of being killed just for being trans. That’s what cinema has to learn.

Be First to Comment