Confessions of a Female Badass is an ongoing column at Curtsies and Hand Grenades where I discuss women in genre cinema.

[TW: Discussions of Rape, Rape Revenge Movies and Rape Culture]

“What is it like to be a Woman?”

Genre cinema frequently asks this question of viewers. In genre it is used as an empathizing technique to ask audiences to identify with a victim and her eventual conflict. By getting viewers to see themselves as the women of these movies filmmakers create a funnel that cycles into tension, horror, action and eventual catharsis through resolution, but what of female audience members? Women already know what it’s like to be a woman. We know the feeling of being followed down a side walk for an uncomfortable amount of time. We understand the jeers of men who make comments about our bodies, because this isn’t something we go to the cinema to feel, but it’s something innate in our own experiences. Rape-revenge cinema takes this question to it’s natural endpoint, and these films at their best emphatically strike back at cultural norms, but far too often they merely reinforce rape and the gendered power dynamics therein. When mixed with the sensationalism of exploitation cinema these movies can tread on shaky ground that sexualize the act of rape, which is a purely evil act in cinematic terms. Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion avoids many of these pitfalls through formal complexity and an understanding that rape is not something to be taken lightly, but instead a problem so paramount in female experiences that an angel of death had to be made for women scorned everywhere. A woman who existed as a blade in the hand of every woman who was ever been sexually taken advantage of by a man. That Woman was named Nami Matsushima (Meiko Kaji), and she was known as the Scorpion.

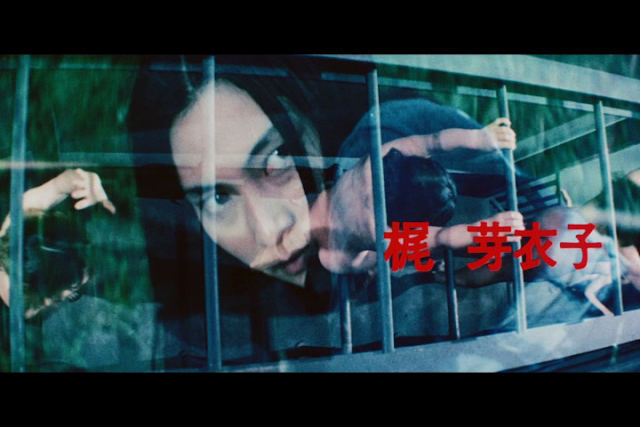

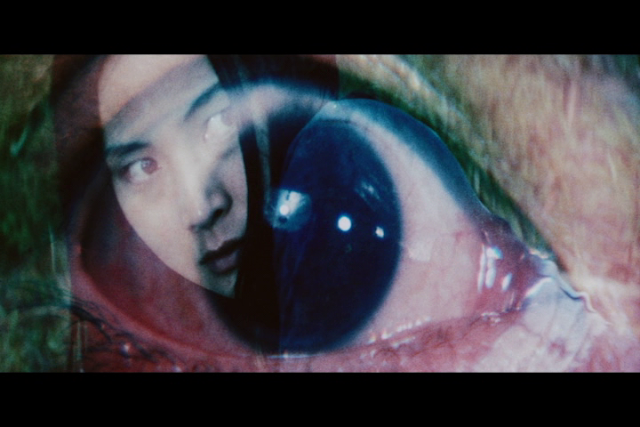

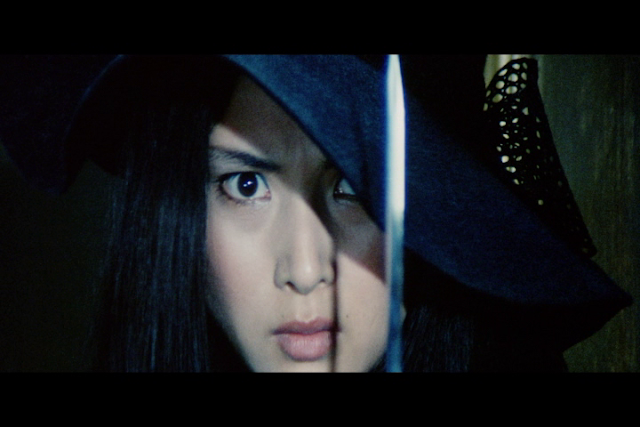

Scoprion is introduced barreling down a field of susuki grass with her friend Yuki (Yayoi Watanabe) as they try to escape the prison. The guards (all men) are hot on their trail with rifles in hand and attack dogs ready to maul. Scorpion and Yuki are thwarted, but in this opening scene Scorpion’s revenge is foretold in her gaze. Meiko Kaji decided to act using only her face and play the role in near silence, a minimalist choice that would prove gravely important to the tone and feeling of director Shunya Ito’s more extravagant set pieces. Kaji’s face grounds every scene, and in close-up her eyes foretell death. There are two images that are created through dissolve in the opening minutes that speak to the films understanding of female P.O.V. in the rape-revenge film. These two images understand whose gaze is violent through objectification and whose gaze is just. In both images Scorpion is leering with determination of her goal of vengeance, but along with her gaze there is the image of nude women prisoners straddling over a bar, and in the other image the bloodshot eye of a lustful man. The first of these images is a rape metaphor. To complete the task of moving over the bar women have to spread their legs and glide over the object. The eye belongs to the man standing directly underneath these women watching them display their bodies as part of a punishment administered by the guards to assert control over their bodies. To control women you take possession of our bodies. This is the power dynamic of rape. Scorpion’s gaze reflects a universal female point of view that ranges from the women in the world of the movie to the women who are merely watching the film. Scorpion is a biblical figure whose vengeance is not only for herself, but for women everywhere. She is a totem, and the movie makes this clear in these early images. Kaiji’s glare is in some small way a statement that our bodies remain our own.

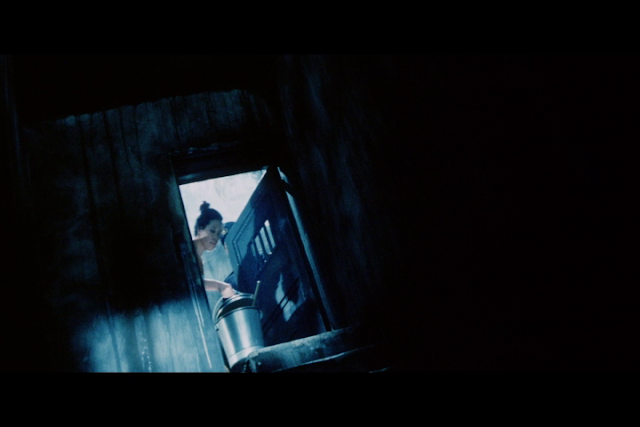

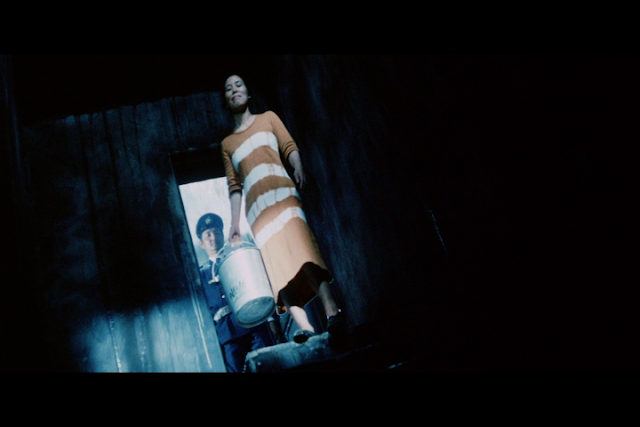

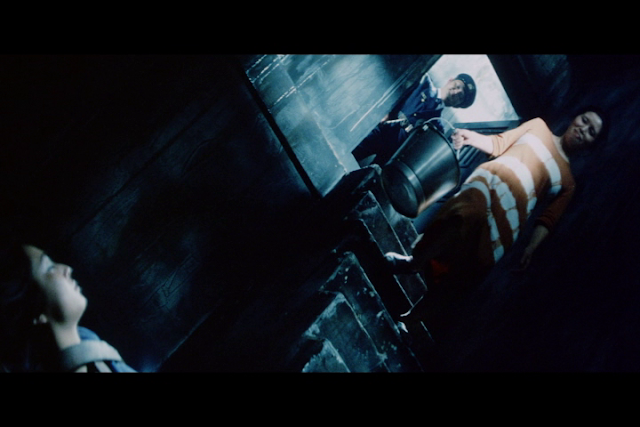

In a 2016 interview with Arrow Video Production Designer Tadayuki Kuwana he stated that he “wanted to create a sense of hell surrounding the prison. I took inspiration from prison camps in World War II for the look of the world surrounding and inhabiting the prison where Scorpion resides”. Kuwana wanted to create depth by using higher ceilings so Scorpion would feel smaller in her surroundings, and this is used to great effect in the first scene following her capture. Scorpion has been locked away in what can only be described as an underground box where the earth bleeds onto her through constant precipitation. She has been hog tied and left there for an undisclosed amount of time, but she hasn’t lost her sense of determination surrounding her vengeance. Her gaze is constant. Ito accompanies Scorpion by having the camera take her eye. When a fellow female prisoner (who has gained some level of privilege in the ranks by selling out other women) arrives to bring her supper the camera stays with Scorpion’s point of view. Ito uses perspective to make us feel like we are in Scorpion’s shoes. The camera looks up at the visitor and then a dutch angle is employed to convey our sense of confinement. Scorpion can’t move to get a better view so the viewer doesn’t either. The understanding that Scorpion is the lead character not just in title, but in form is key to the film’s place as a movie about rape. When movies about rape as a catalyst for revenge stray from the perspective of the abused there is danger in the possible loss of that voice through the mundane trappings of the overworked genre. Films that do travel down that road become less about the consequences and damage of rape and more about violence begetting violence. Where the Scorpion films succeed is in the centralizing of Scorpion as a figure not through narrative, but with the camera as well. The adept image choices and camera movements place us inside Scorpion, and we travel with her rather than at a distance. The viewer is not merely watching, they are being at the same time.

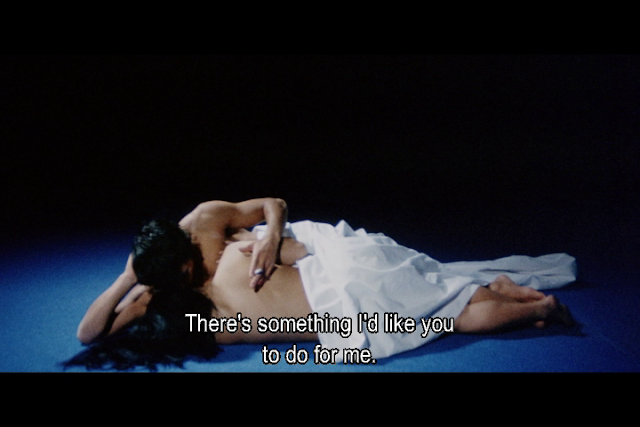

Scorpion’s backstory finds her in prison due to the betrayal of a man. In the deep, comforting blues of an empty space Scorpion has sex with a man she had fallen in love with, and he asks her a favour. The depiction of sex here is in direct contrast with every other sexual encounter in the movie to give a clear view of what is rape and what isn’t. In this earlier scene the camera moves in a dream-like manner of tilted framing and slow-motion with a focus on faces. Scorpion is unwrapped from a blanket to reveal her entire body to her lover and they make love passionately. Like earlier scenes this is shot from her perspective. It was a defining moment in her life, but the man was only using her for his own means. In the first three Female Convict Scorpion movies men are monsters whose sole passions for women only go as far as their usage for their bodies or their skills. Scorpion agrees to do the favour. She infiltrates a den of Marijuana dealers and is subsequently raped. This scene is painful to watch, not in its realism, but in its intentions to break Scorpion. Shunya Ito and Tadayuki Kawana use theatrical techniques to inform the emotional complexity of the scene. Scorpion’s rape is shot from the floor up through a mirror with a focus on her back and tilted, pained face. The faces of her rapists are also visible, contorted and monstrous, with no discernible human qualities. Like exaggerated Clowns with demonic expressions. The scene quickly fades to black and Scorpion’s lover bursts through to arrest the Marijuana dealers for the drug charges as well as a rape charge, but not before he makes a deal with the leader of their drug ring nullifying everything. In a literal heel turn the set uses a revolving door to reveal his dirty deal, and Scorpion’s face is one of utter heartbreak. These scenes are shot from the ground always keeping her face in frame and in focus. Her emotional response is key and Meiko Kaji’s expressive face gives us all we need to know about how hurt she is, and how used up and damaged she felt. This is the moment where Scorpion truly sought after the justice that was owed her. She was used and cast aside after giving away her entire body to this man who had no use for her. She lays on her back and the flames of hell light up underneath her possessing her with the power to take back what was hers. Scorpion finds herself in jail after a failed assassination attempt hours later.

Scorpion’s prison guards are malevolent and spiteful towards her continued disruption of the status quo. They punish Scorpion with solitary confinement in the dank hell, but when she strikes back at her abusers she’s met with more abuse. For Scorpion and the other women in the jailhouse the body isn’t just confined, but lost. The second rape of our lead character occurs less than ten minutes after the flashback sequence of her original betrayal. Like the other scene Scorpion’s point of view is taken into consideration. The camera lies on its back and stares into the eyes of prideful, powerful, evil men. Unlike the first scene this sequence lingers on the act of rape itself showing two gruesome images of penetration with a police baton. The second rape sequence is intended to be the fuel for the viewer’s hatred as well as Scorpion’s. She cracks for the first time in the face of her male oppressors and shows pain in her face, but she ultimately doesn’t lose her gaze or her goal of slaughtering the men of the prison who have taken her life away. The camera finds the right balance of torture, horror, and surrealism with a final twirling image circling her head and finally resting on her eyes. This scene doesn’t sugarcoat the act of rape or sexualize it, but reacts to the bluntness of the act with respect to the victim’s body. Rape is not merely a plot-device in the Scorpion films, but an interrogation on the act and how it specifically relates to women, and the female body. Being a woman watching this film is to be in the trenches of your worst possible nightmares of oppression. Our bodies, spirits and souls expunged in the name of male satisfaction. As Scorpion fights back we live vicariously through her, her blade is ours, and so is her vengeance. Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion is a slow-release bomb towards blatantly criminal patriarchal figures who see women as nothing more than a body or a tool.

Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion complicates itself in its debt to a genre which rarely rose above the gutter. The film lies in the intersection of the rape-revenge horror film and women in prison exploitation pictures. Scorpion is without a doubt exploitation, but exploitation has the ability to get dirty and address problems high-brow films often neglect or soften in favor of a larger audience. Female Prisoner’s greatest complications are when it must align itself to the genres that birthed the movie. For example in the shower scene the camera lingers for what is probably too long on the naked bodies of women, and there is a gratuitous sex scene between two women which isn’t here for much more than titillation. The movie rounds these potentially bankrupt sequences out with a conscious attention to the potential of depth for any scene. The shower sequence is bookended with an actual summoning of a Kwaidan. It’s a show-y sequence which doesn’t play into the films attention to the Woman Scorned Narrative, but distracts from the bodies of Women in the shower. The lesbian scene is followed by the presentation of the double-standard of how sex between men and women is perceived when she is immediately called a slut and beaten down by the prison warden. All of these more difficult scenes of violence against women, both sexual and non-sexual, inform the language of the movie in direct fashion, and because Ito and company paid attention to how things are framed, edited and perceived they never stray from what’s good and bad. The moral obligations of the Female Scorpion movies towards justified violence in the face of oppression stays true.

In what would be the the final punishment of the film Scorpion digs and digs until she drops. While she’s digging the great hole in the Earth her fellow inmates are told to toss dirt in on her, and they slowly grow to hate Scorpion for their own forced punishment of digging. The plot element of women hating each other in the Scorpion film complicates the movie in an interesting way, because the nature of their hatred for one another comes from an ulterior source. The Women only begin to quarrel when scraps of privilege are dangled above their heads by men in positions of power. Some Women look out for each other at all costs, but others buy into the systems of power in the prison system to make their sentences easier.

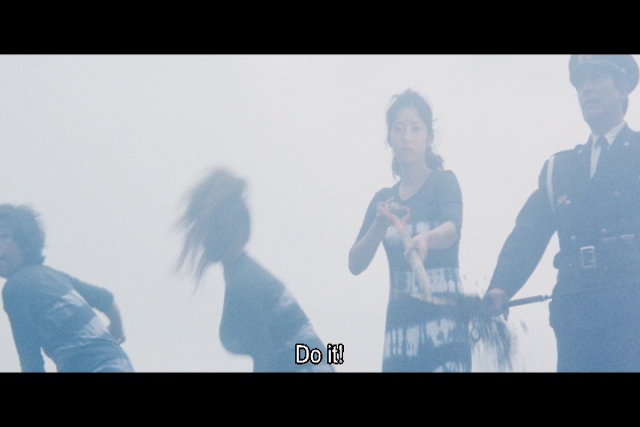

The duality of this female conflict is in the presentation of Yuki and Scorpion who are ride or die gals. Yuki and Scorpion were introduced in the opening minutes trying to escape the prison together, and their bond stays strong throughout the movie. In the dig,dig,dig sequence she is hesitant to throw dirt on her friend until Scorpion acknowledges her and asks her to, because to rebel would mean her punishment and she doesn’t want that for her friend. Ito captures their bond in slow-zoom close-ups and they relay all the information they need to through their faces. When the men try to torture Scorpion by reviving her to dig again once she’s fallen Yuki attacks and sacrifices everything for her friend. She kills a prison guard and brings on a thunderstorm as the women riot.

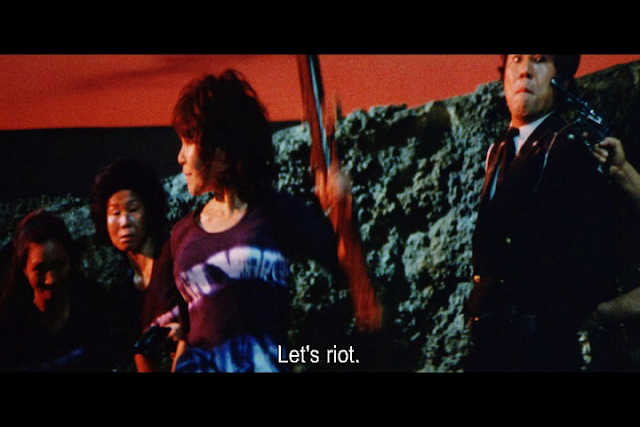

Yuki’s ultimate sacrifice is captured with pure expressionism through set paintings. The sky is tinted orange with fury when the Women riot and shortly after she takes a bullet for Scorpion, the one woman who always looked out for her. After Yuki begins to drift away the sky begins to lose colour fading into a blue before a lightning bolt splits the sky signaling Yuki’s end. The Women do a death dance of joy as they exact their revenge on the men who tortured them for years. The image of the prison Women shaking and screaming, chanting and loosing control of their bodies is powerful in it’s pure unbridled nature. These are Women whose actions, emotions and feelings have been kept in check for god knows how long unleashing everything all at once. However, Scorpion’s vengeance is beyond the prison and for her to find the man who ruined her life she’d need to get to the streets. She escapes among the flames of her inmate sisters as the establishment begins to fall.

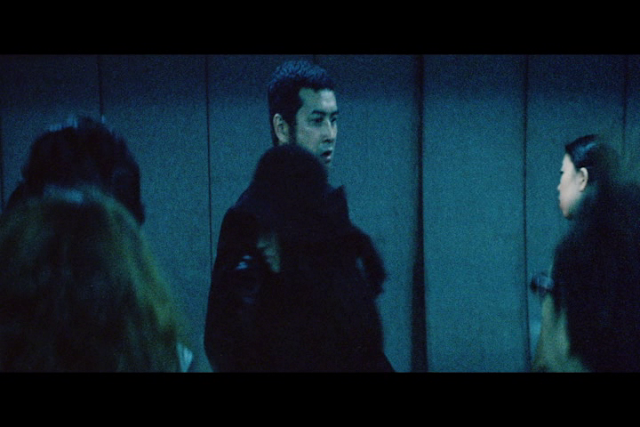

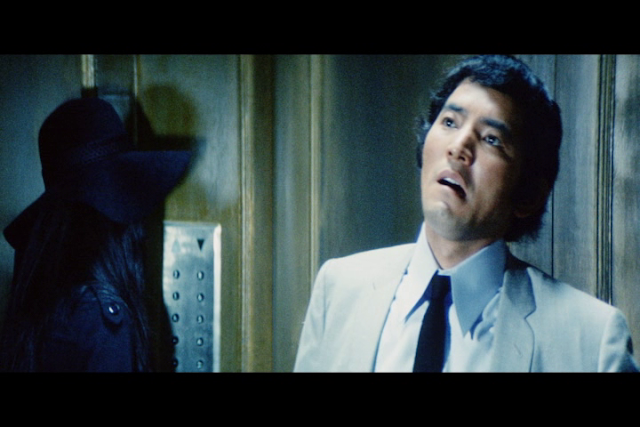

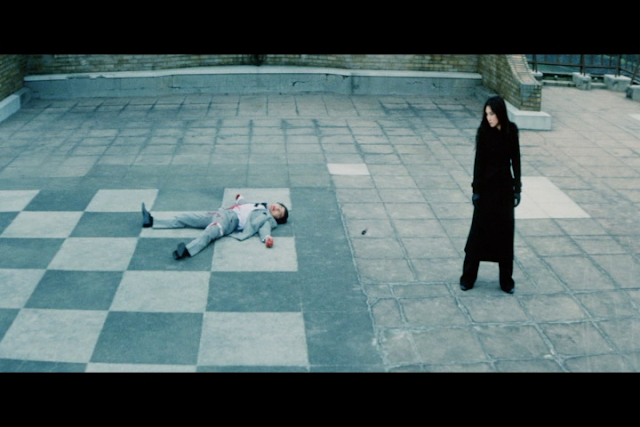

She is dressed for a funeral. Her long black hat shrouds her face and she drifts among the neon lights with ease. She glides like a spectre for the men who wronged her, and they each taste her steel. They lock their expressions in surprised anguish with their shock that a Woman would dare to fight back. Their final faces are created by a Woman who would not take injustice anymore and she extinguished their very lives. Scorpion’s punishment is quick and breathless for all men, except one. She takes her time with the man who set her up and appears in an elevator stabbing him multiple times, but that wasn’t enough, and as he strides out onto the rooftop, covered in blood she stabs him again and again until he’s gone. She stares at him and watches him die. A close-up is used on Meiko Kaji’s face and with her eyes she gives him the same contemptuous look she’s carried throughout the entire film.

When Rape-Revenge films are done well they can be a cathartic outlet for a population without much of an answer as to how to combat rape culture. They can be powerful in their depiction of overcoming a monster, and give those with lingering internal and external wounds a salve for a wound that society refuses to heal. Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion is the apex of the genre in its understanding of the seriousness of rape and the dynamics at play in how and why this act happens. Scorpion is the personification of our scorn, the anger in our hearts and the edge of our knife. She is an avenging reaper whose black wings flap and descend upon rapist men like an Angel of Death. Our Angel of Light.

Be First to Comment