I love films about the relationships women have with one another. The sheer willingness to do anything for another woman, and the strength that comes through in knowing you have an un-severable bond guided linked through a connection of soul. Sisterhood, the very words mean a close relationship among women based on shared experiences, concerns, beliefs. That definition opens up the doors to experiences of women both far and wide, and on the basis of activism, within feminism, sisterhood means a lot. A connection through a struggle and a constant push and pull to unravel oppression. For Marianne and Juliane their sisterhood is through blood and through activism.

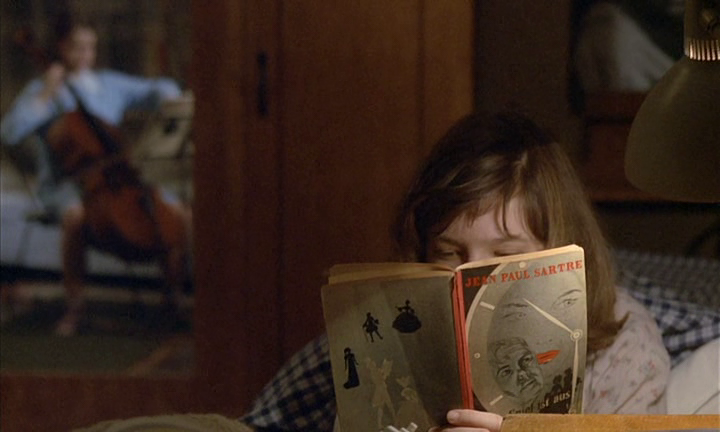

I’m struck by the relative simplicity of Von Trotta’s imagery. Her openness and empathy in showing power of sisterhood through ongoing support. The recurring image of Marianne and Juliane is one of sisters embracing when they need it. It’s an image of love, of power, of purity. When Marianne goes to jail for terrorist activities related to her feminism her sister supports her without any reservations. She’ll put her hand up to glass dividing them as they discuss her incarceration, and make a joke about how her sisters hands feel cold, relieving the tension of her stressful situation. In a flashback sequence both sisters meet up in the girls bathroom of their schooling to shed tears over Holocaust footage, knowing their people did this. Their activism is born in this moment, but it also shows Von Trotta’s humanity towards the girls as they know they must never allow this to happen again, but through it all they would have each others support. Another moment of sisterly interaction has both women swapping sweaters after Marianne visits her in prison for the first time, and Juliane needing something warmer. This act of giving what was on her back to her sister is emblematic of their relationship. They would do anything for one another at all times. It’s a simple moment, but speaks to a larger loving relationship between the two, and Von Trotta’s ability to get across meaning through workmanlike imagery is essentially what makes Marianne and Julianne such a striking, devastating film on relationships, sisterhood, feminism, systems of oppression, and motherhood.

That strength in imagery carries over into all facets of the film’s political intentions. The scene I mentioned above about the holocaust showed actual footage in a classroom demonstration, but Von Trotta does not shy away from her countries history of violence. It is curious then why Marianne chooses to fight for her own rights through means of violence. When she weeps with her sister in the girls bathroom after seeing these images one would think she would lean towards pacifism in her own activism as these images seriously affected her, but she becomes a terrorist. It may then make sense that she sees those who were oppressed at the time of World War II and identified with them so greatly that she assumed the only way to fight this level of violence is to then work with those tools. This is a question the film doesn’t answer, and the ambiguity of her activism is interesting to me, and more powerful than a straight response, because it opens up debate among viewers.

Marianne and Julianne’s feminism is equally interpreted through simplistic, raw, but nonetheless affecting imagery that she also gave to their sisterly relationship. In one flashback sequence when Julianne is writing about Marianne’s upbringing the film shows the two of them at a dance. A dance that Marianne had trouble going to because she refused to wear a dress, but eventually gave into. When the DJ begins to mutter over the microphone it’s time for a boys and girls dance she approaches the dancefloor, but not with a boy, by herself. The looks of confusion that spread across the adults faces at this dance show this act as something of a rebellion. She didn’t need anyone. She’d be an independent woman. Von Trotta chooses to close this scene with an elderly woman smiling on at her as if to say feminism has always been present in Germany. Marianne’s later death in the movie is given the same raw treatment that she has shown throughout all of the movie. When Marianne’s decaying corpse is opened to view for the public she hasn’t been made beautiful, but instead her body is wrecked with decomposition, and her face frozen in an image of terror. Von Trotta doesn’t sugarcoat that Marianne’s death is a political one, and by showing Marianne’s broken body for what it is, the tragedy of the scene overflows. Julianne’s grief is also delivered in a similar manner with consistent close-ups of weeping, moaning and sorrow. The scenes between the two sisters early on code the grief of the picture as something significant, but the acting of Jutte Lampe is something else entirely, tapping into Rowlands-esque levels of emotiveness. Von Trotta is wonderfully laid back in these moments, and let’s Lampe act out her breakdown, and this creates another lasting, straightforward, blunt image. That’s the lasting effect of her camera, and the thing I’m most impressed with. She shows no inclinations towards breaking the mold, but she knows how to get across the message she intended to by simply showing and not overdoing.There’s simply no need to shoot something differently when a close-up of a face gets across everything you’d need to know about the pain of the scene.

The final feminist coded strand of this picture is within motherhood, and choice. The film is bookended by abortion and choosing to raise a child. Marianne and Julianne begins with an introduction of Julianne as a feminist woman. She is fighting for the right to choose through her abortion activism. At the beginning she is seen making signs and handing out pamplets to get the word out to other German’s about her personal choice to have children whenever she wants, something all cis women should have. Her sister Marianne has a child, but hasn’t seen him since he was two years old, and ultimately decided she wasn’t in the right place to become a mother at the time. We see the child throughout, but he’s used more as a totem for a woman’s choice than an actual character. If the movie has any weaknesses it’s in this segment where Von Trotta’s falls prey to cramming a bit too much into her movie. The connective notions of choice are tied up a little too cleanly in the closing moments when Julianne chooses to adopt Marianne’s long lost son after losing her sister. This could have maybe ended on a stronger note with the loss of Marianne and having Julianne fight for her sisters reputation as a great woman, but nevertheless Von Trotta pulls a final great moment out of this otherwise loosely connected storyline issue in the final frames. When Marianne’s son and Julianne sit down for the first time he tears a picture of his mother up, because he resents her having left him, much to Juliane’s dismay. She tells him that she was a great woman, and he listens. He wants to know everything. Julianne looks at him and the film closes on a still image of her face. Women are always telling the stories of other women. Our history isn’t buried when we’re talking about each other. I’m brought back to something Kathleen Hanna once said about creating art for women and fighting through the difficulty of it all. In The Punk Singer, she simply said “Women would understand”. Von Trotta made a picture that answers that call, and in her images she made a movie women would understand & relate to whether you’re an activist or not, a mother or not, a sister or not. This film is implicitly about women, and I’m grateful there are movies about that connection we have as women to people like ourselves.

Be First to Comment