“What are you?”

“…a monster”

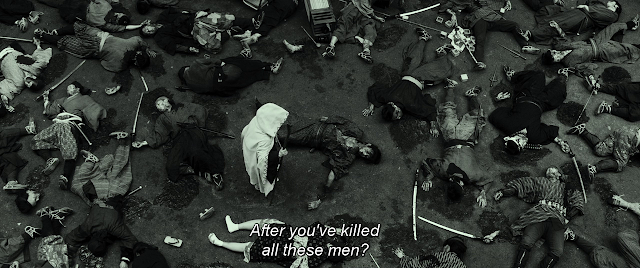

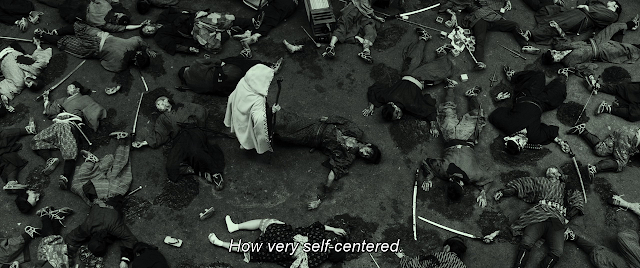

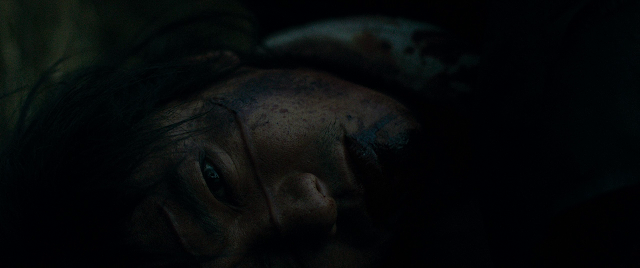

In the opening moments of Takashi Miike’s newest film, Blade of the Immortal, Manji (Takuya Kimura) slaughters one hundred men in an act of revenge for having just seen his sister murdered at the hands of a nameless villain. It’s a beautiful sequence draped in a colour-palette that can only be described as black and cobalt with fluid fight choreography and excellent geographic mapping so the viewer is never lost in the cut or the location. But behind all the violence on screen are insert shots (scar-tissue on a wounded eye, a splash of blood across a bare chest) that make viewers never forget what they are watching is indeed a violent act. In an auto-critique of his own career Miike brandishes himself as the monster by personifying his 100 films with the 100 men that were killed in an act of revenge. Miike, himself, is known as a provocateur of abstract surrealism that frequently mingles with sex, drugs, and violence. The question remains however, drizzled in the machinations of his work asking viewers and himself alike, “What is violence for?”, and with Blade of the Immortal Takashi Miike once again gives suggestions, while letting the answer gracefully float away into the air.

After satisfying his bloodlust and his quest for revenge Manji is cursed with immortality. For each life he has taken he must live out that life-span giving weight to his violent actions. Each nameless, faceless unimportant character slaughtered in the opening comes with consequences. No act of violence exists in a nutshell. Violence extends and poisons beyond itself. This is why Manji is cursed and why Miike subtly condemns his viewers for taking part in the violent cinema he has created. Takashi Miike is an auteurist only in the sense that he is a moralist and within his cinema characters reckon with violence as an extension of their personalities, their job and their life. In Takashi Miike’s best film, Dead or Alive 2: Birds, a pair of yakuza hitmen (played by V-Cinema icons Show Aikawa and Riki Takeuchi) hole up in an elementary school while they are on the run. Despite their peaceful setting violence interjects, and tears at the fabric of their reality. In a sly scene of audience critique and on the nature of persistent violence; the yakuza hitmen perform a play for the elementary schoolchildren and throughout this play there are frequent edits between the audience laughing at the absurdities on stage mixed with violent attacks from the yakuza in real time who are hunting Show and Riki. We’re the audience. Does violence then exist because we lap it up like warm tea? Or is it something more elemental in the human psyche? These questions are unclear, but he’s been grappling with them throughout his entire career.

|

| Dead or Alive 2: Birds |

|

| Dead or Alive 2: Birds |

Takashi Miike’s interest in unraveling the ball of yarn on violent cinema can perhaps be traced to his interest in the films of the Japanese genre filmmaker Kinji Fukasaku from the 1970s. Fukasaku made his name directing yakuza pictures which depicted a post-war Japan’s crisis of masculinity in the wake of the atomic bomb. In the opening scene of the first Battles Without Honor or Humanity film American G.I.s are depicted in an act of rape on a young Japanese Woman, in an intended image to double as metaphor for the state of Japan after the atomic attack from the United States. What is first portrayed as a matter of regaining a national identity through Yakuza action against the evil American infantrymen quickly becomes a parable of a snake eating its own tail in the pursuit of not only a masculine position of power, but also monetary gain and control over the resources of Japanese cities. But these films unspool in a way that eventually shows the Yakuza not as an incendiary force for justice, but as a domino effect where each and every Japanese man is taking to an early grave, and the women who support these men are left to pick up the pieces. In these pictures, yakuza business is handled through economic pressure and violence inflicted upon rival gangs by other hitmen, but when powerful yakuza fall prey to death’s cool hand and eager young men take their place a blood debt has to be repaid so a cycle of revenge repeats itself and eats on Japanese men with no real sign of stoppage. Fukasaku argues with these films that the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki essentially opened a wound that would never stop bleeding.

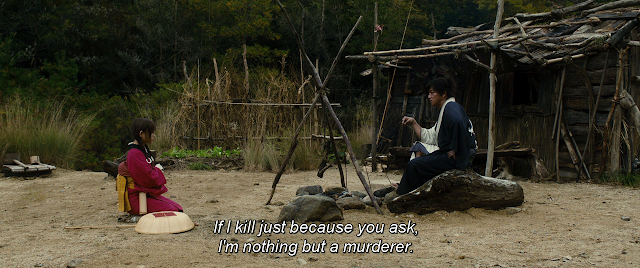

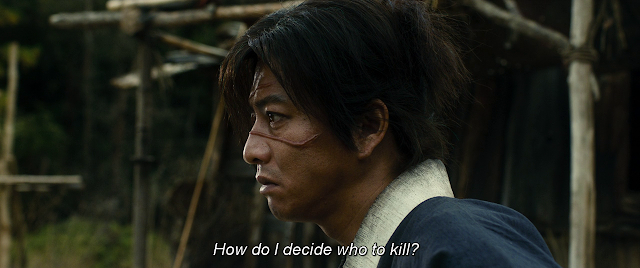

With Blade of the Immortal, Takashi Miike is making a similar argument, but in the past tense of the edo period Samurai picture. This is before World War II, but the symptom where violence only begets more bloodshed is firmly in place. When Manji is eventually confronted by a young girl named Rin (Hana Sugisaki) to commit an act of violence on behalf of her murdered family Manji is hesitant, because with his new immortality he doesn’t take life lightly anymore and he doesn’t kill for any simple reason, but she gets to him. A family resemblance to his younger sister convinces him to take on the task of avenging Rin’s family, but not before discussing the logic behind killing someone to the poor girl. He wants her to understand that if she commits an act of revenge so too will someone do the same to her. If blood is spilled it must be paid back evenly. Manji carries with him the scars of grief and battle and they do not go away. Everyone dies eventually except the man who has killed so often he becomes a legend. A fairy tale. A god. A Demon.

In Blade of the Immortal, a frequently occurring technique is the insert shot of flesh torn in half, scarred, burned or mutilated in a way that it doesn’t look human any longer. Unlike the gutless invulnerability of superheros in Western Culture Manji heals slowly, and he carries the battle on his body by way of scars that are always there to remind him of the unjust murders he committed in the name of his fallen sister. These people Manji fights, now in the name of Rin, are equally torn apart by violence. One swordsman appears to have three heads, but he merely carries corpses on his back. A close-up is used to show his disfigured face, and much like Manji his body reflects violence. It’s a vessel for which life ends. Along their journey Manji and Rin confront many others, some with cleaner skin than others, but Manji wilts under the blood, viscous and ripped apart flesh of his body until there’s hardly anything left. Miike doesn’t pull any punches as things reach a climax (with a few bloated, unnecessary side plots here and there) frequently zeroing in on Manji’s immortal body as it falls apart, but impossibly perseveres. When Manji finally confronts the man who wronged Rin, Kagehisa Anotsu (Sota Fukushi), he’s barely a man anymore, more zombie than alive, and there is no elegant duel between sword wielding warriors. It is merely an act of execution, a job being completed, and a loss of life. It is with blunt honesty that Miike displays this final dance not as something worthwhile or justifiable, but another violent act in a long string of violent acts that Manji has committed during his lifetime, and some day Rin will die because of his actions. This is the parable of violence. This is man’s curse.

Be First to Comment